In The Loneliest Place: The Allure Of The Homme Fatale In Stranger By The Lakeby Craig J. Clark

By Yasmina Tawil

“People who aren’t familiar with this milieu could think this is a kind of science-fiction film.” –writer/director Alain Guiraudie

Of all the films that came out of the 2013 Cannes Film Festival—a remarkably strong year, in retrospect—the one I keep returning to, curiously enough, is from a filmmaker whose prior work was entirely unknown to me at the time. Emerging from a field that included highly anticipated films from Ethan and Joel Coen, Sofia Coppola, Asghar Farhadi, Jim Jarmusch, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Hirokazu Koreeda, Alexander Payne, Roman Polanski, Nicolas Winding Refn, and Steven Soderbergh (to name ten), Alain Guiraudie’s Stranger By The Lake muscled its way onto my must-see list on the basis of what is admittedly a mixed festival dispatch and stayed there until it came to Blu-ray one year later. I’ve since watched it three more times, including a much-welcome repertory screening at my local university, and can easily see myself revisiting it every couple of years until I die—or the disc wears out, whichever happens first.

Part of the attraction for me is that films that deal so directly—and so frankly—with gay male desire aren’t always easy to come by. (It’s also rare for them to get much traction at prestigious festivals like Cannes, where Guiraudie won the Directing Prize in the Un Certain Regard section and Stranger beat out Palme d’Or winner Blue Is The Warmest Color and Soderbergh’s Behind The Candelabra for the Queer Palm, an award whose existence is a welcome sign these kinds of films are no longer getting swept under the rug.) The other part of the attraction is the way Guiraudie takes full advantage of his premise to give the viewer an eyeful of his buff leads, who spend much of the film’s running time partially or completely in the buff.

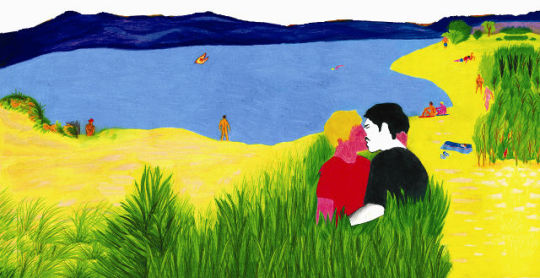

Since it’s unlikely I’ll be visiting a nude beach in the South of France anytime soon, Stranger By The Lake scratches the same voyeuristic itch as William Friedkin’s Cruising, which steeped itself in New York’s leather bar scene just before AIDS forever altered the playing field. And sure enough, the specter of AIDS haunts this film as well. Drawn to both the idyllic cruising spot that serves as its sole location and Michel (Christophe Paou), the handsome, mustachioed stranger he encounters there, Franck (Pierre Deladonchamps), the film’s impetuous protagonist, is cavalier about condom use to the point that he’s essentially taking his life in his hands every time he has sex. Then again, he does that anyway, since he continues to pursue the object of his infatuation even after watching Michel drown his lover Pascal (François Labarthe, one of the film’s art directors) late one night. Sure, the guy has an Adonis-like body, but that’s taking amour fou to the extreme.

•

“It’s hard to tell how Dix feels about anything. None of us would figure him out.” –Mel, Dix’s loyal-to-a-fault agent

A useful point of comparison is Nicholas Ray’s seminal 1950 noir In A Lonely Place, in which would-be Hollywood starlet Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame, then married to Ray, although not for much longer) falls in love with her neighbor, hot-tempered screenwriter Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart, whose Santana Productions produced the film), after she provides him with an alibi when he’s suspected of murder. When asked why she would go to bat for someone she hardly knows, she quips that she likes his face, but the more she gets to know him, the more she comes to love the whole man, warts and all. This despite the warnings of well-meaning friends (“There’s something wrong with him,” says one) and the police captain who has Dix pegged as his prime suspect. “Someday you’ll find out who your friend is,” he tells Laurel. “I only hope it’s not too late.”

Franck and Michel have their own run-ins with the law in the form of the bothersome Inspector Damroder (Jérôme Chappatte), who arrives on the scene when Pascal’s body is discovered four days after his murder. In the interim, the two men have become an item, but Franck is simultaneously frustrated by Michel’s insistence that their relationship be purely sexual and careful not to press the issue too hard lest he share Pascal’s watery fate. Like Laurel, Franck protects Michel when they’re confronted by Damroder, but doing so not only makes him an accessory after the fact, but also a potential suspect in the eyes of the law. On top of that, it’s been established that Michel knows Franck was at the lake at the time of the murder, so the young man’s reluctance to finger him seems doubly misguided. Does he honestly believe they can have a future together or is he that blinded by lust, which he has somehow mistaken for love?

Having seen what Michel is capable of with his own eyes, Franck shouldn’t need any warnings, but Henri (Patrick d’Assumçao), the overweight (and allegedly straight) logger who comes to the beach every day to hang out, but never goes into the woods to cruise, tries to talk some sense into Franck regardless. “Maybe you’re too gaga to see it, but he’s weird,” Henri says, echoing Laurel’s friend. “I’d be scared if I were you.” Then again, according to Henri, Franck should be more wary in general since their very first conversation is about the silurus—a large species of catfish—that is said to inhabit the lake and is rumored to be a 15-footer. The silurus comes up again the day Pascal’s body is found and Franck and Henri are the only ones who show up at the lake and stick around long enough to have a conversation. “You want to swim where a man drowned?” the bewildered Henri asks. “Maybe not today,” Franck replies, “but in a few days.”

This blithe disregard for his own safety is a reflection of Franck’s behavior in the days immediately following the murder. Instead of going to the police to report what he saw or staying the hell away, he goes right back to the lake, irrationally hoping Michel will return to the scene of his crime. Both days, Franck sees Pascal’s car, which hasn’t been moved from its spot in the parking area, and notes the presence of his towel and clothing on the beach, which no one else acknowledges. Then, at the end of the second day, after everyone else has left and Franck has all but given up hope (he’s even started making overtures to Henri, who’s amenable to being friends, at least), Michel emerges from the lake like a vision and walks straight up to Franck, who is thrilled his dream man has appeared in the flesh and is equally unconcerned about having oral sex without a condom. (If anybody watching had any doubts that Michel = the silurus = HIV, this and later scenes where they have unprotected sex should lay them to rest.)

•

“But in the end we’re stupid. We want to get trapped. We need ties, we need firm points of reference. We need to be the way we are. It’s not worth having regrets.” –the narrator of Guiraudie’s 1994 short Straight Ahead Until Morning

One key difference between Stranger By The Lake and In A Lonely Place is while the former is told almost exclusively from Franck’s point of view, the latter starts out following Dix before switching to Laurel’s perspective as she begins to have doubts about his innocence. Once the dreamy weeks of semi-domestic bliss are behind them—and the plum screenwriting assignment she’s been helping him with is reaching its natural endpoint—his temper starts to flare up again as the ongoing police scrutiny intensifies. She even has to stop him from braining a motorist with a rock when they have a mild fender bender (for which Dix is entirely to blame). What she isn’t privy to is the way he anonymously makes things up to his victims after he’s cooled off. Even his own agent doesn’t know about these private acts of contrition, but he does recognize that Dix’s periodic blowups are part and parcel of his so-called genius. “You knew he was dynamite,” Mel tells Laurel. “He has to explode sometimes.” What’s unfortunate is that his erratic behavior drives away the one person in the world capable of keeping him on an even keel. Which brings us to the other place where the two stories diverge.

While Laurel, having wised up to Dix’s emotional instability and seen his violent temperament in full flower, stage-manages her narrow escape from his clutches, Franck doesn’t fully comprehend how much danger he’s in until Michel kills two more people, including Henri, who willingly sacrifices himself to save the mixed-up young man to whom he’s grown attached. His death turns out to be entirely in vain, though, for after initially running from Michel, Franck does a turnabout and calls out to him, tentatively at first, then with more insistence. Does he do this because he’s alone in the dark, nearly naked, with Henri’s blood literally on his hands, or is it because his mad love for Michel trumps his fear? As Inspector Damroder says during one of his interrogations, “You guys have a strange way of loving each other sometimes.” This signals that the behavior of all homosexuals is alien to him—he’s definitely one who would consider this film to be “science fiction”—but Franck’s is particularly puzzling. The way Deladonchamps plays him, he’s ruled by contradictory moods and self-destructive impulses, but once he’s in Michel’s sights, Franck can’t help but be drawn in like a moth to a flame.

Likewise, I return to Stranger By The Lake because of the danger lurking within, not in spite of it. As superficial and callous as Guiraudie makes his characters out to be, how they interact has the ring of authenticity to it, especially in the moments when Franck mingles with anyone else who has come to the lake to cruise. Whatever drives him to act the way he does is just as clouded in mystery as Michel’s unexplained need for discretion. I’ve long taken it as read that Michel is the film’s title character, but in his own way, Franck also chooses to be a stranger.