Gregg Araki, Eternal Teenager by Charles Bramesco

By Yasmina Tawil

“Life is lonely, boring and dumb.” —The Doom Generation

“I feel like a gerbil smothered in Richard Gere’s butthole.” —also The Doom Generation

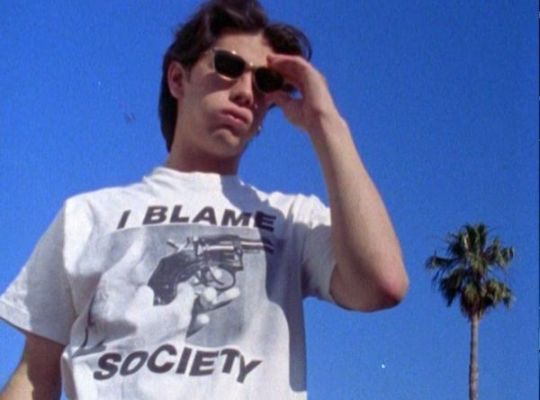

Gregg Araki likes young people. He likes their asymmetrical dyed hair and ripped denim, the tight fabrics that look like placeholders waiting to be ripped off. He likes shoegaze and dream-pop music, Cocteau Twins and Ride and the Smiths. He likes drugs, whether that’s the de-stressing release of a hand-rolled joint, the supercharged kick from a bump of coke, or the rush from the right colored pill. He likes junk food, low-budget grindhouse movies, and joyriding. And he likes sex— all different kinds, with boys and/or girls, with multiple partners, often at once.

Araki clutters his films with signifiers of his many fixations, like a student doodling in the margins of their marble composition notebook or taping up magazine clip-outs to the inside of their locker. It’s all mashed together into one overstuffed barrage of out-there allusions, conspicuously cool stylistic flourishes, and endlessly quotable catchphrases. In the case of Totally Fucked Up, The Doom Generation, and Nowhere—three of the director’s early films that fans have colloquially bound together as the “Teenage Apocalypse trilogy”—those qualities of adolescence and freewheeling messiness are inextricably linked. The soul of Araki’s trilogy, the key to its rowdy pubescent essence, lives in the flaws that make these films as perversely charismatic as they are. To be a teenager is to be a fuck-up, and nobody fucks up more beautifully or entertainingly than Gregg Araki.

His earliest films were highly experimental, blithely erotic projects slapped together for next to nothing, suffused with their director/writer’s passions and fetishes. But even as Araki advanced out of both his twenties and the five-figure budget range, his unapologetic teen spirit polarized audiences. It outright alienated Roger Ebert, who notoriously slapped The Doom Generation with a zero-star rating and called its director “a stylist who can use concepts like iconography and irony to weasel away from his material.” The esteemed critic objected to the constant sarcasm and thick stew of references, and while his charges may very well stick, they’re also integral to the film’s representation of teenager-dom.

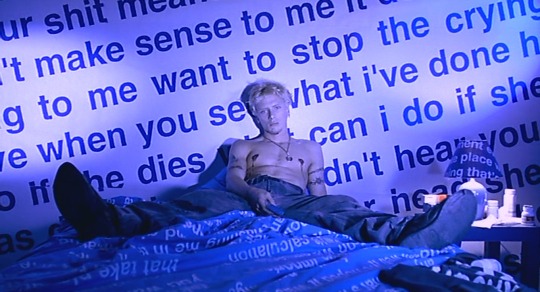

Totally Fucked Up is a Handicam-shot chronicle of queer teenage life in fifteen parts, The Doom Generation follows a nasty-tempered ménage à trois on a bloodsoaked spree across the California sprawl, and Nowhere tracks the evolution of a relationship between two polyamorous bisexual teenagers during a secret alien invasion. All three films share the foremost objective of replicating what it feels like to be young, punk, and horny. Rather than merely depicting the radical mood swings and world-is-ending dramatics of the pre-adulthood years, Araki’s films actively perform adolescence.

Nobody could possibly deny that Araki’s trilogy has a whirling chaos to it, but rather than the mark of an undisciplined filmmaker, this constitutes a deliberate aesthetic choice befitting the material. The Doom Generation’s combustible trio on the lam calls to mind the previous year’s Natural Born Killers as well as Bonnie and Clyde, Badlands, and a host of forgotten teensploitation flicks that all gibe with Araki’s arrested-development reference points. What, after all, could be more recognizably teenage than bearing your influences and personal faves for all the world to admire? Nowhere (named after the 1990 EP from shoegaze godfathers Ride) applies that more-is-more-is-more philosophy to its narrative structure, which jumps from character to character whenever the plot threatens to stagnate even for a moment.

His films are terminally chill when they’re not manic, finding quiet interludes (emphasis on ludes) for fake deep philosophizing. “Ever feel like reality is more twisted than dreams?” wonders James Duval as The Doom Generation’s cuckolded Jordan White. Araki’s not affecting the irony that his opponents so frequently accuse him of; while he’s not sincerely asking the question (even he’s not that stoned), he’s sincerely presenting the act of asking it. The director understands what would possess the character to say such a thing, and because he treats the line of dialogue as valid instead of an object for mockery, the overall tone comes off as sneering snark. The closest Araki’s characters get to an undying devotion of love is “I hope we die simultaneously, like in a car wreck or a nuclear bomb blast or something.” Grappling with meaning far beyond one’s sphere of comprehension is also a fundamental component of the teenage experience.

Oh, and the sex. There is, to put it mildly, a lot of doing-it in le cinema de Araki. He’s unabashed about the pleasure he takes in the image of the body, male and female alike (Araki has self-identified as bisexual), though most of his scenes aren’t oriented around mutual pleasure or even romance. There’s a hectic, desperate sting to the furtive rutting that goes on between the main couple of Nowhere, the assorted lovers of Totally Fucked Up, and the central threesome of The Doom Generation. The movements are fast, sloppy, driven by hunger. Araki skirts any unearned romanticization of youth sexuality and exposes a truth often denied by cinema: teenagers are not necessarily better at boning, they just try harder. Jordan and Amy Blue (a standout Rose McGowan) share the following exchange as they lie in postcoital cool-down:

“Don’t you think sex is, like, totally strange? Just the whole idea of it: all fleshy and stiff, inserted in these warm squishy places?”

“I think it’s more powerful than we’d like it to be.”

“It’s fuckin’ trippy, that’s for sure.”

Araki welcomes the awkwardness, the uncomfortableness, all the wrinkles of lovemaking that get ironed out with experience. The unsanitized experience, warts and all (occasionally literally), make it to the screen intact.

If the gratuitous sex or hormonal shifts in tone don’t get his detractors bristling, Araki’s retro razor-blade dialogue can still come off as overbearing. To acolytes of colorful Z-grade cinema scripts, lines like “You’re like a life support system for a cock!” qualify as sacred psalms. To non-believers, however, a one-liner as gleefully trashy as “This party’s about as much fun as an ingrown butt hair” sounds like the handiwork of a man infatuated with his own voice. But again, that characteristic, however amateurish, emulates the teen preoccupation with slang. Youths form social groups and individual identity through highly specialized vernacular; if it sounds like Araki’s speaking an insular language that only his chosen people can pick up, that means he’s on the right track.

The MTV-on-even-more-drugs highs and lo-fi lows, the incorrigible horndoggery, the too-cool-for-school dialogue, the efforts to do everything at the same time — it all comes back to Araki’s core nature as a trier. The Teenage Apocalypse trilogy finds Araki trying extremely hard to be cool, and this may be the most quintessentially teenage, nakedly honest aspect of his entire oeuvre. In his trilogy, Araki strives to produce a pop-culture object that will transfix the same burnout punks he fetishizes in his films, an obsession he clearly shares. That desire to be liked, to fit in, to be like your idols—that’s the central pillar of school-aged emotional immaturity.

Across the scores and scores of movies about young people, the default authorial viewpoint has been that of someone who’s been through it all. Tragedies and triumphs are kept in perspective, and by the time the end credits roll, our protagonist has probably learned a valuable lesson or two about the world of adulthood. But the most honest, true-to-life portrayals of teens don’t come from the worldly-wise stance of an adult looking back; they should hum with the ragged-around-the-edges, work-in-progress feeling of that specific life phase. Araki’s Teenage Apocalypse trilogy gives us cinema’s closest approximation of an impossible dream: a professional film about the agony and ecstasy (and Ecstasy) of being a teenager, straight from the source. Ah, to be young, hot and turned-on forever…