From An Early Frost to The Normal Heart: The Shifting Sands of the AIDS Narrative on Filmby Craig J. Clark

By Yasmina Tawil

“People are dying so fast that it’s like what I imagine being in a war would be like.”

–volunteer nurse Hedy Straus in the 1987 documentary short Living With AIDS

By the time Ronald Reagan deigned to mention AIDS publicly for the first time in a press conference on September 17, 1985, it was known in some circles that the virus that causes it had been ravaging the gay community for more than four years. In the interim, while the medical and scientific communities scrambled to get a grip on the epidemic and fought for the government funding needed to do so properly, gay writers and filmmakers responded to the health crisis in their own way—by creating plays and films that humanized its victims and had the potential to educate the American public about the need for compassion and swift action.

One of the most immediate of these responses was Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart, which the outspoken writer/activist—a founding member of Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1982, when the disease was still known as GRID, or Gay-Related Immunity Disease—started writing in 1983 and saw staged to great acclaim at New York City’s Public Theater in the spring of 1985. Another project with a similar gestation period was the pioneering TV movie An Early Frost, broadcast by NBC that fall after co-writers and partners Ron Cowen and Daniel Lipman—who later went to develop Queer As Folk for Showtime—went through 15 drafts with the network over a year and a half. And first-time filmmaker Bill Sherwood’s low-budget indie Parting Glances was shot in 1984—as evidenced by the new releases lining the wall in one scene set at a trendy record store—but didn’t get released until early 1986. Snapshots of a time when there was a great deal of misinformation about AIDS and the people it affected, all three remain urgent dispatches from the front lines of the struggle. But to keep them straight, it’s helpful to take them in the order they reached the screen, touching on a few other milestones along the way.

“I’m sure you’ve heard of Acquired Immunity Deficiency Syndrome.”

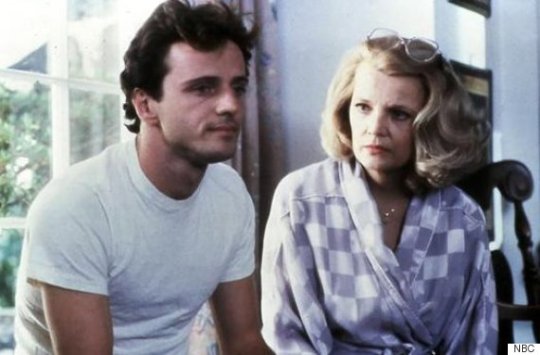

For all its good intentions, An Early Frost wasn’t the first feature film about AIDS. In his seminal text, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality In The Movies, Vito Russo gives that distinction to Arthur J. Bressan, Jr.’s Buddies, and he’s supported by Raymond Murray’s Images in the Dark: An Encyclopedia Of Gay And Lesbian Film And Video. According to Murray’s book, however, Buddies was never released on video and it continues to be unavailable to stream or purchase, which has rendered it as invisible today as AIDS sufferers were to the general public three decades ago. By contrast, An Early Frost was put out on DVD in 2006, complete with a commentary by Cowen, Lipman, and lead actor Aidan Quinn, plus the documentary short Living With AIDS, which was filmed by producer/director/editor Tina DeFeliciantonio in 1985 and broadcast on PBS a couple years later. A huge ratings-getter, An Early Frost beat out Monday Night Football to be the top-rated show of the night, capturing one-third of the total viewing audience when it premiered. Today, it takes viewers back to a time when AIDS was a death sentence for nearly everyone who contracted it and effectively outed those who were still in the closet.

That’s the dilemma faced by hotshot Chicago lawyer Michael Pierson (Quinn), who’s just been made a partner at his law firm when he gets sick. This causes friction with his lover of two years, Peter (D.W. Moffett), particularly when Peter confesses he’s been unfaithful. But that’s nothing compared to how his family back home reacts to the double whammy of finding out their prodigal son is not only gay, but also has “the gay plague” (one of many euphemisms for the disease that get bandied about in these films). Mother Kate (Gena Rowlands) is confused, but tries her best to be understanding, which is the opposite of father Nick (Ben Gazzara), a straight-shooting lumber company owner whose first instinct is to strike Michael when he drops the bomb. (And Peter wonders why he never came out to them before.) And thanks to unfounded fears about how the virus is spread, which many shared at the time, his pregnant sister deliberately keeps her distance and freaks out when her son runs up to him for a hug. The fictional characters weren’t the only ones alarmed by the prospect of physical contact with an AIDS patient, though. Over and above not showing two gay men kissing—or even sharing a bed—NBC executives also objected to a kiss between Michael and his grandmother (Sylvia Sidney), which is doubly ironic since it occurs in the scene where she reassures him that “It’s a disease, not a disgrace.”

In spite of the network’s skittishness and the concessions Cowen and Lipman had to make, they still managed to break a lot of ground and won one of An Early Frost’s four Primetime Emmy Awards (out of 14 nominations) for their efforts. Also nominated: Quinn, Rowlands, Gazzara, Sidney, and director John Erman. The most deserving, however, may be John Glover for his flamboyant turn as Victor, an irrepressibly chipper AIDS patient Michael meets in group, whose outrageous outlook on the disease is fueled by the fact that he’s been living with it for two years. Within a handful of scenes, Glover sketches in a fully realized character who transcends stereotype and whose fighting spirit is an inspiration for Michael—at least as long as he sticks around. It was a big deal that Cowen and Lipman stuck to their guns and made sure their protagonist made it to the closing credits alive, but there were far more Victors in the world who didn’t.

“Is it true that the man over there is dying?”

An Early Frost ends on a note of uncertainty as Michael, having reconciled with his parents and recovered from a bout with toxoplasmosis, hops in a cab and rides off into the inky blackness, eager to return to his high-paying job and the life-extending health insurance it affords him. All it would take, though, is the right opportunistic infection (like Kaposi’s Sarcoma, which is seen on Victor and another man in their group) for that to all go away. That’s also the reality faced by Nick, the character with AIDS in Bill Sherwood’s Parting Glances, which came along soon after and turned out to be the writer/director’s one and only film, due to his death of AIDS in 1990. A successful musician-turned-virtual shut-in, Nick is played by a shockingly young Steve Buscemi, who brings a sardonic nonchalance to the role. Introduced watching MTV with the sound off, waiting for his band’s music video to get played, he’s also shown rebelling against the health-food regimen his ex-boyfriend Michael (Richard Ganoung) has him on—in lieu of the medications that didn’t exist yet—and taping his video will, which doubles as a coming-out to his father.

As central as he is to the narrative, Nick isn’t the main character—that would, in fact, be Michael, a frustrated writer down in the dumps because Robert, his lover of six years, is all set to leave the country for the foreseeable future. Still, the most pointed scenes in the film are the ones that involve Nick, as when he’s provoked by a ghostly apparition into putting in an appearance at Robert’s going-away party, where he’s taken for something of a ghost himself. Meanwhile, Michael weighs his options: Stay faithful to Robert, go back to Nick, or respond to the overtures of a cute record-store clerk a full decade his junior. He ends the film by taking an air taxi to Fire Island after receiving a cryptic phone call from Nick. It’s a place Sherwood has taken the viewer a number of times before in brief flashbacks showing Nick and Michael getting one over on an insufferable queen with a house on the island. Far from being Nick’s resting place, though, it’s where he’s decided to open the next chapter of his life, however long or short it may be.

“What do you think happens when we die?”

“We get to have sex again.”

The beach scenes in Parting Glances are echoed in 1989’s Longtime Companion, one of a number of AIDS films to take the form of a history lesson. Covering eight years in the lives of a close-knit group of gay men as the disease decimates them, playwright Craig Lucas’s screenplay starts with the fateful July 4th weekend in 1981 (a time of joyous celebration of youth and vitality, set to the buoyant strains of Blondie’s “The Tide Is High”), when the New York Times published its first article about crisis, headlined “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” Alarming as it is, it doesn’t raise any red flags for those summering on Fire Island (i.e. the majority of the film’s characters), but there are some who sense the dark clouds on the horizon. From there, Lucas advances their stories incrementally, going year by year to chart the progress of the epidemic and how it comes to dominate—and, in some cases, take—their lives. Along the way, he hits the expected mile-markers: the youngest among them being the first stricken, the first sighting of someone with KS, the false sense of security stemming from the isolation of the virus, the donning of gowns and masks during hospital visits, the drug cocktails that do as much harm as good, the healthy individuals who go from calling Gay Men’s Health Crisis for help for their loved ones to volunteering for the organization. And it all circles back to Fire Island, which is eerily empty in the summer of 1989. There, the ones who are left look ahead to the future and hope a cure won’t be too long in arriving.

In the pantheon of AIDS films, Longtime Companion is significant for being the first dramatic feature on the subject to be nominated for an Academy Award, for Bruce Davison’s touching portrayal of a man who watches impotently while his partner slowly wastes away. (The year before, Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman’s Common Threads: Stories From The Quilt took home the award for Best Documentary.) Campbell Scott is also a standout as a trainer who has to overcome his paranoia in the face of the disease to support his friends and loved ones. And just as An Early Frost features Bill Paxton and Terry O’Quinn in supporting roles (the latter as the doctor who gives Michael his fateful diagnosis) and the mostly unknown cast of Parting Glances includes Kathy Kinney in her screen debut (a full decade before she found fame as Drew Carey’s nemesis Mimi on The Drew Carey Show), so too does Tony Shalhoub show up in Longtime Companion (also as a doctor).

The most star-studded AIDS film, though, has to be HBO’s 1993 adaptation of And The Band Played On. Based on the 1987 nonfiction bestseller of the same name by Randy Shilts, the film focuses on the efforts of government agencies like the Centers for Disease Control, the National Cancer Institute, and the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases to battle the virus—and occasionally each other. Mirroring An Early Frost’s success, it wound up being nominated for 14 Primetime Emmy Awards, including one for Matthew Modine in the Lead Actor category and supporting nods for Alan Alda, Richard Gere, Swoosie Kurtz, Ian McKellen, and Lily Tomlin. And one of its three wins was for Outstanding Made for Television Movie, prefiguring The Normal Heart’s win in the same category two decades later.

The high regard for And The Band Played On is well-founded, but having treated the subject so thoroughly, subsequent films about the epidemic’s early days became few and far between. Following the example of the Oscar-winning Philadelphia, released the same year, many of the AIDS films of the ’90s and ’00s were contemporary dramas and dramedies. Some were adaptation of plays (Paul Rudnick’s Jeffrey, Terrence McNally’s Love! Valour! Compassion!), while others took the form of angry screeds (Gregg Araki’s The Living End) or arty provocations (Derek Jarman’s Blue). As life with HIV/AIDS turned out to be more than just the fancy of an imaginative dramatist, the impetus to fictionalize its inception fell by the wayside. Filling in the gaps were hard-hitting documentaries like David Weissman and Bill Weber’s We Were Here, which relates the queer community’s reaction to the epidemic in San Francisco (significantly, where Living With AIDS was shot), Jeffrey Schwarz’s Vito, which covers Vito Russo’s career as a cultural critic until it morphs into an AIDS film when Russo is diagnosed, and David France’s Oscar-nominated How To Survive A Plague, about the ten-year struggle of gay activists in America to get the government to take the AIDS epidemic seriously enough to adequately fund research into a cure.

“Nobody with half a brain gets involved with gay politics. There’s no room for criticism.”

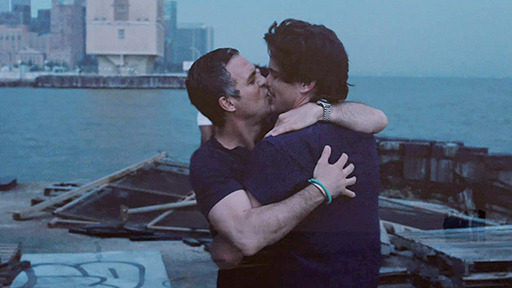

One of the lynchpins of that effort was Larry Kramer, who founded ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) in 1987, the year the death toll from the disease reached half a million worldwide. By the time HBO turned his play The Normal Heart into a film in 2014, the World Health Organization had raised that figure to 34 million, with 36.9 million more believed to be living with HIV/AIDS. Clearly, the time for another history lesson was nigh, but what was a wake-up call in 1985 is something of a museum piece today, even if the urgency of its message has not diminished. That it borders on stridency at times is partly due to Kramer’s bluntness (subtlety was far from his greatest concern), but director Ryan Murphy (television’s standard-bearer for campy excess) shoulders some of the blame as well. Regardless, they recruited a top-flight group of actors to bring the play to the small screen, chief among them Mark Ruffalo as Kramer stand-in Ned Weeks, a writer who’s already far from Mr. Popular with the Fire Island crowd after the publication of his novel—which goes unnamed but is a clear ringer for Kramer’s controversial 1978 book Faggots and, as a friend tells Ned, “made us look terrible”—when the onset of the epidemic gives him something else to sound off about.

With its Fire Island setting and hedonistic displays, The Normal Heart’s pre-title sequence neatly mirrors the opening of Longtime Companion—just substitute Tom Tom Club’s “Genius Of Love” for “The Tide Is High”—and even has Ned read the same New York Times article on the ferry ride back to the city, where he has his first encounter with a Kaposi’s Sarcoma sufferer in the waiting room of Dr. Emma (Julia Roberts), the “holy terror in a wheelchair” who gets him up to speed on the severity of the crisis. From there, Kramer and Murphy dramatize Weeks’ swift political awakening and the founding of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, for which he becomes the de facto spokesperson, much to the dismay of its closeted president, Bruce (Taylor Kitsch). The supporting cast also includes Matt Bomer as Felix, a young New York Times style writer who becomes Ned’s lover; Love! Valour! Compassion! director Joe Mantello as fellow board member Mickey; Jim Parsons as Tommy, a hospital administrator who often plays the catty devil’s advocate; and Alfred Molina as Ned’s older brother Ben, a lawyer who’s browbeaten into doing pro bono work for the organization. All get their big Emmy moments (six of the film’s 16 nominations were for its performances), but the quieter scenes—like Tommy’s description of his Rolodex ritual and Ned and Felix’s ahead-of-its-time marriage—are the ones that make the bigger impact.

“I wonder if there’s going to be this, like, wave of monogamy because of all of this.”

As long as there’s no cure for HIV/AIDS, writers and filmmakers will continue to tell stories about its impact on the gay community. Case in point: writer/director Chris Mason Johnson’s Test, which opened in New York just a few weeks after The Normal Heart’s HBO premiere. Serving as the low-key yin to The Normal Heart’s bombastic yang—or possibly the Parting Glances to its Early Frost—Test takes place in San Francisco in the year 1985, when the first blood test for the disease was developed. As Bill Sherwood did before him, Johnson limits his perspective, focusing on Frankie (professional dancer Scott Marlowe making his screen debut), an understudy for a modern ballet dance troupe who frets about the prospect of getting AIDS and judgmentally chides fellow dancer Todd (Matthew Risch) for sleeping around and occasionally taking money for sex.

Frankie’s no stranger to casual sex himself, though, as evidenced by his acceptance of a discreetly filmed blow job from a neighbor selling vintage clothing. (It’s never stated outright, but the implication is that the clothes are his dead lover’s.) And when he finally gets his big break—significantly, when the lead dancer comes down with an unspecified ailment—he and Todd go out clubbing to celebrate and Frankie picks up a cute guy with whom he has vigorous, unprotected sex. The turning point comes when the HIV test goes into use and, after expressing concerns about its confidentiality, Frankie takes it and is on pins and needles while he waits two weeks for the results. His anxiety is akin to Cleo’s in Agnès Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7, but the sense of relief when the test comes back negative is tinged with the knowledge that this is a bullet he’ll have to keep dodging for the foreseeable future. With the combination of the right partner and an openness to using condoms, though, he just might get to see it.

Test’s low-key roll-out—after playing the festival circuit for a year, it had the briefest of theatrical runs—is indicative of how gay-centric AIDS films have been sidelined since their commercial peak in the 1990s. To get a wide release and Academy Award recognition these days, one seemingly needs to have a relatable hetero protagonist—a reality Craig Lucas keenly foresaw in his directorial debut, 2005’s The Dying Gaul, about a grief-stricken Hollywood writer faced with having to alter the screenplay he wrote following the loss of his longtime companion to be more palatable to straight audiences. Then again, the home for such stories may very well be the small screen, as evidenced by An Early Frost and HBO’s star-laden triptych of And The Band Played On, Angels In America, and The Normal Heart. Who needs Oscars when the Emmys are there for the taking?