Filming the Unfilmable: On Six Versions of Emily Brontë's ‘Wuthering Heights’ by Soheil Rezayazdi

By Yasmina Tawil

[Editor’s note: One of the six Wuthering Heights adaptations discussed in this essay is Andrea Arnold’s 2011 version, which is distributed by Oscilloscope Pictures. The opinion expressed below was developed independently of Oscilloscope and is entirely reflective of the author’s point of view.]

I needed a love story in my life. If not love, at least an obsession. Something to pass the time and occupy the mind. I’d spent much of the summer simmering in heartache, the kind that makes you feel young again—and not in a good way. I got used to weeping behind sunglasses on the subway. I remembered the wild, irrational agony of a text message ignored. I felt the total loss of self-control we call “emotional vulnerability.”

All that crazed energy with nowhere to go. Amidst a thick melancholic fog, I found a tattered 1970 paperback of Wuthering Heights in the foyer of my apartment building. I knew the Kate Bush karaoke anthem and the gist of the novel as a Romeo & Juliet-esque story of star-crossed lovers. This’ll do, I thought.

Those 400 pages held something else entirely: a knotty saga of love souring into resentment, exploitation, and violent grief. Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel doesn’t balm a broken heart, I learned; it hardens it. Our principal lovers, Heathcliff and Catherine, spend most of the book in a histrionic rage. They manipulate and blame one another for their love’s collapse. Catherine marries another man; Heathcliff seduces the other man’s sister just to rattle the cage. Their love curdles into something ghastly.

And then, of course, one of them dies. And we still have 200 more pages of book to read.

Despite the romance-novel reputation, Wuthering Heights goes down about as bitter as any pill I’ve taken. Brontë depicts passion as a dangerous double-edged sword; it intoxicates, sure, but it also turns humans into monsters. Her characters personify the adage “hurt people hurt people.” Heroes become villains in a multi-generational tale that balances a dozen key characters, rests on an elaborate nesting-doll structure, and offers a master class in cruelty.

///

This could never be a film. That was my first thought, anyway, upon reading the novel. Wuthering Heights doesn’t bear the signs of a classic “unfilmable novel” like Naked Lunch. The action is grounded in the real world, and Brontë’s prose keeps things plot-driven and outside the realm of non-visual ideas. This is a story about humans who love and betray one another in the English countryside. It sounds simple enough, but Brontë presents at least three major headaches for any filmmaker.

First, we have those unlikeable leads. Catherine is a self-involved “wild, wicked slip of a girl,” and Heathcliff has “an almost idiotic excess of unsociable moroseness.” How could a two-hour film capture both their childhood tenderness and their sociopathic savagery while still luring audiences to identify with (and root for) their ill-fated love? Plenty of films depict Byronic anti-heroes, but Heathcliff is a unique challenge. He grows so unsympathetic that he’d alienate any viewer in search of a diverting love story.

Second, the scope of the novel seems like a fool’s errand to capture in a feature. The book charts three generations of the Earnshaw and Linton families, from 1771 to 1803. Most printings include a family tree to help the reader keep track of all the marriages and children. The book hits the reset button after Catherine’s death, introducing new protagonists with their own inner lives for its second act. At 400 pages, Wuthering Heights lacks the intimidating heft of a true epic like War and Peace. The book covers so much narrative action, however, and asks us to invest in so many characters that it seems unfeasible to synthesize all that material into a single sitting.

Lastly, we have the nightmare of casting this story. Barring an extreme use of aging makeup, anyone adapting Wuthering Heights would have to cast multiple actors for up to six characters: Heathcliff, Catherine, Hareton, Hindley, Edgar, and Ellen. Heathcliff ages from seven to 37 in the book, Ellen from 14 to 44. Aging on the page is easy. On the screen, though, it’s a practical problem. Do you cake the cast in makeup—always a gamble—or do you cast Little/Big Catherine, Little/Big Heathcliff, Little/Big Edgar until the audience gets vertigo? A rigorous adaptation of Wuthering Heights would not only introduce new characters halfway through the film; it’d also introduce new actors to play the characters we already know. The very idea sounds like an experiment in jarring a film viewer.

///

Despite the onerous material, many have tried. To date, a fan of Emily Brontë can gorge on more than 20 screen adaptations of her novel—feature films, miniseries, TV shows—from across the world. Take your pick: an MTV movie co-starring Katherine Heigl; a ’60s Bollywood epic; a 200-episode Filipino series; and, of course, the Masterpiece Theater treatment.

This is some seriously curious endurance for a story this nasty and complicated. The novel’s central conflicts are timeless: passion vs. pragmatism, city vs. country folk, race and class, the corrosive power of jealousy. Elements of the novel have permeated the stories we’ve told for the past 170 years. How many times have we seen a woman forced to choose between two men: one rugged and risky, the other boring and safe? The ingredients of Wuthering Heights have become the stuff of myth. The book as a whole, however, seems an intractable thing for filmmakers.

Arthouse auteurs, studio craftsmen, and hacks alike have attempted to turn Wuthering Heights into a feature. This analysis focuses on six major adaptations from William Wyler (1939), Luis Buñuel (1954), Jacques Rivette (1985), Yoshishige Yoshida (1988), Peter Kosminsky (1992), and Andrea Arnold (2011).

I was compelled to learn how screenwriters and directors have wrestled with this material. It became a fitting distraction from my lovelorn angst. I didn’t find a traditionally satisfying love story in Wuthering Heights. What I did find, though, was an obsession.

///

1939: Wuthering Heights

“I have never felt any obligation to be faithful to every word of authors like Emily Brontë […] My film Wuthering Heights only used a portion of the novel because the book goes on after the film ends and gets repetitious.” – William Wyler

William Wyler’s Wuthering Heights remains the default—if not the most respected—adaptation of Brontë’s novel. Wyler’s is the only adaptation produced by a major American studio with a cast of marquee names, and it’s the only one to win an Oscar. Produced by Samuel Goldwyn, the film has the big-budget bonafides of a sweeping Hollywood romance. Goldwyn, Wyler, and their screenwriters transformed a sour novel into a product casual filmgoers still consume nearly 80 years later.

They did it by chopping the novel in half and sanitizing Heathcliff. The film maintains the book’s very literary structure, in which a peripheral character (Nelly) relays the story of Catherine and Heathcliff to a curious traveler (Mr. Lockwood). From there, Wyler reshapes the material to portray Heathcliff as a flawed but sympathetic hero. Early in the film, for example, we witness a fight between Heathcliff and Catherine’s brother, Hindley. Hindley has a lame horse and demands to switch horses with Heathcliff. When Heathcliff protests, Hindley barks “Give him to me or I’ll tell my father you boasted you’d turn me out of doors when he dies!” and hits Heathcliff with a rock. There’s no ambiguity here: Hindley’s a tyrant, Heathcliff a victim.

On the page things are much muddier. As Brontë wrote it, it’s Heathcliff who has the lame horse and demands that the two switch. “You must exchange horses with me: I don’t like mine,” he tells Hindley, “and if you won’t I shall tell your father of the three thrashings you’ve given me this week.” Here, Heathcliff shouts the threats and steals the horse. The scene ends and neither boy earns our sympathies. Heathcliff comes across as a manipulative aggressor, Hindley as a violent bully.

That type of icky ambiguity has no place in the 1939 film, which literally sanitizes Heathcliff. As Wyler said, Goldwyn “wanted his pictures to be clean and glamorous,” so he fought to have Heathcliff appear less dirty in the film. Goldwyn also fought for an absurdly incongruous final image of the two leads reunited in heaven, walking on a cloud. “[Goldwyn] had somebody else do it and that shot is still in the picture,” Wyler later said. “It’s an awful shot.”

Wyler and his screenwriters solve the casting and narrative dilemmas with a simple, crude solution: Just ignore the second half of the book. As the first major adaptation of Brontë’s novel, this film set this precedent for all future versions. To date, only two theatrical films have told the second half of the story, in which Heathcliff descends into pure villainy as he terrorizes a younger generation of lovers. Brontë sought to show the lingering effects of a wild passion snuffed out by external forces. She also had another story to tell: a second love triangle between Catherine’s daughter, Heathcliff’s son, and Hindley’s son. Her novel shows how one generation can poison the well for another, and how, despite all that toxicity, some still find happiness. Taking Wyler’s lead, most adaptations have erased this crucial part of the story.

///

1954: Abismos de pasión

Interviewer: I believe someone told me you wanted to remake [your own version of] Wuthering Heights.

Luis Buñuel: To make it better. I would film it with a good cast in England or France.

For his take on Brontë, Luis Buñuel relocates Wuthering Heights to 19th century Mexico and distills the narrative even further. His film covers about one-quarter of the novel—from Heathcliff’s return after years abroad until Catherine’s death. Buñuel said he was drawn to this material, like other surrealist thinkers, for “its climate of passion, for l’amour fou that destroys everything.” As such, he focuses on the most emotionally heightened stretch of the novel and eschews the rest. Thus, no aging characters, no shifting protagonists, no family tree to memorize.

True to the novel in tone if not in narrative, Buñuel tosses the first 100 pages of the book—including the framing device and any depiction of the leads as children—to show these characters at their most vicious. His version is all brutality and irrational passion: in essence, the emotions that linger in the mind as you read the novel. As Raymond Durgnant wrote in his 1967 book on Buñuel, “The love of Heathcliff and Cathy, cursed, mutually destructive, yet in the end achieved, could not but fascinate the director of L’Age d’Or.”

In at least few memorable moments, Buñuel imbues this gothic romance with the surrealist visual logic of Un Chien Andalou and his other great works. During the film’s wholly invented final scene, for example, Heathcliff hallucinates an image of Catherine in a wedding dress, arms stretched out as if to invite him. Buñuel then cuts from Catherine to a graphic match of her brother with a shotgun, who shoots our hero seconds before the credits roll.

Abismos de pasión, as the director admits, is a compromised work. Despite the promise of an iconoclast like Buñuel handling this material, the final product feels hamstrung. To begin, the film’s producers forced a rather middling cast on Buñuel. Along with being far too old for the roles, the actors fail to convey the fiery passion needed to sell this story (it was a “sad cast imposed on me,” in Buñuel’s words). The producers also bathe the film in an incessant score that detracts from the film’s depiction of l’amour fou, a love so dark it kills those consumed by it. Buñuel didn’t supervise the music and was stunned to find it smothering the final cut of his film. Last, Buñuel also disliked the setting, which again the producers demanded in order to get the film made. As the introductory quote indicates, if he could have made the film again, under different circumstances, he would have.

Among cinephiles, Abismos de pasión would likely rank as the best adaptation of Brontë’s novel. It’s telling, then, that the most acclaimed version of Wuthering Heights also covers the least of the novel’s action. Given how little of the book it depicts, Buñuel’s film strains the definition of “adaptation.” Instead, it draws on a single feverish stretch of the novel to capture the totality of the book’s spirit. Perhaps that’s the best one can hope for with Wuthering Heights.

///

1985: Hurlevent

“We either simplified or deleted. In my opinion, some important scenes are missing towards the end, in particular when it comes to Catherine’s long illness, which is really too elliptical—and it is so powerful in the novel.” – Jacques Rivette

The sparest film explored here, Hurlevent strips away the melodramatic flourishes of Wyler’s film and transports Wuthering Heights to the French countryside in the 1930s. Jacques Rivette is on record as “hating” Wyler’s film, and his take on the novel feels in many ways like a direct revision of the 1939 film.

“Wyler’s movie is vaguely faithful to the novel, in the letter, but makes no sense whatsoever with all those ball scenes sprinkled everywhere,” Rivette said in interviews, comparing the film to a Jane Austen novel.

Hurlevent, like the previous two films, doesn’t touch the second half of Wuthering Heights. Instead, Rivette opens with our leads as young adults living under Hindley, an alcoholic brute mourning his wife. He splits the difference between the 1939 and 1954 adaptations; his film covers about one-third of the novel, whereas those cover one-half and one-fourth, respectively. Rivette eliminates the need to cast multiple actors in key roles by reducing the plot to a three-year span (as opposed to the novel’s 31-year timetable). We’re left with just the bare essentials of the book’s first half: the central love triangle, Linton’s sister Isabella, and the housekeeper Nelly.

Though it covers just one-third of the novel, Hurlevent barrels through this story to arrive at Catherine’s death in two hours. The elliptical nature of the film was, in part, budgetary. Rivette, known for his opuses like Celine and Julie Go Boating, didn’t have the time or money for such a production: “Otherwise,” he’s said, “I might have made a three or three-and-a-half hour movie, like I usually do.” The film we have, instead, rushes through Brontë’s book in a strangely bloodless fashion. The deliberate, low-key performances don’t help this material ignite either. Here, for example, is a typical piece of dialogue from the portion of Wuthering Heights covered in Hurlevent:

“Oh, I’m burning! I wish I were out of doors! I wish I were a girl again, half savage and hardy, and free; and laughing at injuries, not maddening under them! Why am I so changed? Why does my blood rush into a hell of tumult at a few words?”

Rivette translates all that sound and fury into a laconic, motionless feature – what Rivette scholar Mary Wiles generously calls “theatricality through the tableau.” He converts every exclamation point in the Brontë text (and there are hundreds) into an ellipsis. His film emphasizes the icy gamesmanship between Catherine and Heathcliff, a key element of the novel ignored by Wyler. What he loses is the hysterical passion that possesses these characters to love and loathe one another with equal force. Aside from a few indelible dream sequences, Hurlevent offers a muted take on very loud material.

“It was really a problematic movie,” Rivette said in 2003. “Actually, I don’t know what to think of it. I haven’t seen it since and would be very much afraid of seeing it now.”

///

“Problematic movie” could describe all three adaptations of Wuthering Heights I’d seen thus far. Even with directors as gifted as Wyler, Buñuel, and Rivette, Brontë’s novel remains a stubborn thing. All three films ignore the second half of the novel, and all three suffered production woes that left them maimed by producers and tight budgets. The productions, as others have noted, seem cursed, as though haunted by the ghosts of Brontë, Heathcliff, and Catherine.

Despite—or maybe because of—this history of partial, imperfect tellings, the adaptations have continued. No one’s gotten it quite right. The definitive take on Wuthering Heights remains up for grabs, and filmmakers up to the challenge. The audience is there, too: The novel’s obsessives continue to fixate on this mystifying story. Wuthering Heights envelops us. We obsess over this saga like it was our own failed relationship. Where did it go wrong, we wonder? Why couldn’t they make it work? We reread the novel and seek out the films, in part, to find answers to those questions, both for Heathcliff and Catherine and in our own lives.

///

1988: Arashi ga oka

“[Arashi ga oka] I made as pure cinema, just as a cinematic challenge.” – Yoshishige Yoshida

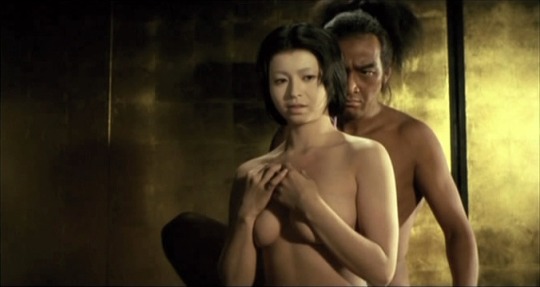

Yoshishige Yoshida was the first filmmaker to tackle the totality of Wuthering Heights in a feature. His film, Arashi ga oka, played in competition at Cannes, and it stands as a singular take on Brontë. He sets the story in medieval Japan on the slopes of a volcano. In a rare 1991 interview, Yoshida said he wanted to both challenge the romanticism of the Wyler film and pay tribute to Buñuel’s adaptation. The film certainly does both: His tale foregrounds the brutality that erupts as a byproduct of Catherine and Heathcliff’s doomed love.

Yoshida covers the two key generations of this story without the casting nightmares mentioned up top. He does it with an elegant expansion and contraction of the text. We see our leads as children for just four minutes of screen time. From there, Yoshida shifts all the action of the novel’s first half onto the leads as young adults.

He does the same in the second act. We see our new leads as children, but their key scenes all occur as teenagers played by the same pair of actors. The characters age and emerge organically, without absurd aging makeup or a perpetually rotating cast. Yoshida also eliminates the second act’s love triangle to get this story down to feature length. The Isabella character kills herself before she gives birth to Heathcliff’s son; thus, the second generation consists of a straightforward union between Hareton and Cathy under Heathcliff’s tyranny. The calculus here adds up: To tell the full story in 140 minutes, Yoshida figures it’s more important to illustrate Heathcliff’s cruelty to the young lovers than it is to recreate the Hareton-Cathy-Linton love triangle. As a reader, you’re far more likely to recall and have strong feelings about the former than the latter.

Arashi ga oka is an outlier among feature-length versions of Wuthering Heights. The film’s violence and sexuality distance it from most adaptations and the novel itself. Surely this is the only version of Wuthering Heights with violent sword battles. Above all, Yoshida uses Brontë as a blueprint for his larger ideas on Japan’s Shinto religion and geopolitical place in the world. According to film writer John Collick, who interviewed Yoshida for a book on literary adaptations, Heathcliff’s arrival into the lives of these characters “represents the continual intrusion of western society into Japan.” Collick writes that Yoshida had core ideas in mind for the film:

“The relationship between a small, isolated tradition-bound community and a larger, powerful and threatening cosmos; the stranger who is transformed into a god and who disrupts the social order; and finally the traditional Shinto belief in the genii loci or spirits of nature.”

In short, Yoshida borrows the plot points of Wuthering Heights for a thematically rich interrogation of Japanese culture. His film hits the novel’s narrative beats, but it uses them primarily as a framework to explore his own preoccupations. This, I’d argue, makes Arashi ga oka one of the more interesting versions of Wuthering Heights, even if it bypasses many of the granular details of the book.

///

1992: Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights

Interviewer: Is there anything about your career you regret?

Peter Kosminsky: Doing a remake of Wuthering Heights in 1992, when I had only ever made one drama. It was the biggest mistake of my life, and I repented at great leisure.

Four years later, Peter Kosminsky became the second—and, to date, final—director to adapt both halves of Wuthering Heights into a theatrical feature. He sets the action against the traditional English-moorland backdrop and covers the entire novel with the patience of a pushy restaurant busser. Though it works around the novel’s tough-to-adapt issues in notable ways, it’s nonetheless, to quote Kosminsky, “a truly terrible adaptation of Wuthering Heights.”

The film tinkers with the book’s flashback structure in a unique fashion. It preserves the Lockwood character, unlike most adaptations, but the film itself is narrated not by Nelly to Lockwood but by “Emily Brontë” to us, the audience. It’s an awkward move, but it allows Kosminsky to use a narrator to compress the novel’s action without the labored Nelly/Lockwood framework. He further truncates the early pages by reducing the childhood years of the novel to a mere three minutes of screentime. Like Yoshida, Kosminsky has Catherine and Heathcliff age quickly to young adulthood, where the actors, particularly Fiennes, can pass for anywhere between 17 and 37 years old. Like most adaptations, this one breezes past the flashback structure and childhood years to arrive faster at the histrionics of the story’s middle section.

The boldest gambit here is Kosminsky’s move to cast Juliette Binoche as both Catherine and her daughter Cathy. From an adaptation standpoint, Binoche’s double role is an inventive solution to a difficult text. Kosminsky doesn’t have to introduce a new central cast member halfway through the film; instead, he eases the viewer into Wuthering Height’s second half with many of the same actors in place. The casting also speaks to Heathcliff’s motivation for tormenting the young lovers after his own doomed romance. There’s a real power in seeing Fiennes berate the same actor with whom he was in love in the film’s first hour.

The film is, nevertheless, a slipshod rush-job of a movie. Kosminsky blazes through the latter half of the novel with a lip-service rendering of the younger generation’s love triangle. Brontë’s wrote a story of one generation refusing to repeat the alluringly romantic mistakes of their elders. Little Cathy, wrote Joyce Carol Oates in her ode to the novel, “exhibits an altogether welcome instinct for self-knowledge and compromise – for the subtle stratagems of adult life – that have been, all along, absent in her elders.” Kosminsky’s film fails to capture this, the raison d'être of the novel’s second half. Instead, the second hour is the mere afterbirth of the first, where the “real” action takes place before Catherine’s death.

What we get, instead, is a parade of plot points. Despite the painfully melodramatic tone—a favorite moment: Binoche stares at a storm cloud/metaphor of doom and intones “I don’t care!” to the sky—there isn’t much feeling behind this visual book report. Kosminsky had never made a theatrical feature before, and he regrets starting with a work this layered and emotionally complex. It’s “not a good film in any way,” he said years later.

///

2011: Wuthering Heights

“A lot of people have something to say about Wuthering Heights, but nobody quite nails it. I knew that I wouldn’t nail it either, but I couldn’t resist the opportunity to spend some time with that unfathomable story.” – Andrea Arnold

Reviled by book purists and casual filmgoers, Andrea Arnold’s Wuthering Heights has the hallmarks of a “gritty, modern reboot.” Her film is all atmosphere: Moths flutter against window panes, windswept hair floats in slow motion. Arnold applies her signature poetic realist vision to a world defined by boredom and brutality. It’s a silly metric, but more than half of the film’s 300 Amazon reviews are one-star rants with phrases like “I have a copy of every version of this movie and this is THE WORST!”

“I don’t like that film,” Arnold said earlier this year, adding to the chorus. “I think you’re allowed to not like your own film.”

Arnold strips the book of its frenzied dialogue for an experiential take that stresses the harshness of 18th century rural life. She wants us to feel the mud, the cold, the dark. Arnold isolates moments in time, often in shallow focus close-up, to emphasize the slow-moving ennui of this setting. If most versions of Wuthering Heights are overstuffed with plot and unearned emotional arcs, hers is a radical course-correct: It immerses us in ambience with a neglect for story. Most directors force-feed the audience; Arnold leaves them hungry, and cold.

The film works around the novel’s adaptation roadblocks like most films discussed here. Arnold luxuriates in the novel’s first 200 pages, cutting Lockwood, the flashback structure, and the second half of the book to focus on our leads as children and young adults. She casts two actors for the parts of Heathcliff, Catherine, and Edgar, and she devotes far more time to these characters as children than other adaptations. Arnold’s fix for this unfilmable text should sound familiar: Everything gets easier when you ignore the second half of the book.

If she simplifies the novel, she doesn’t sanitize it. Hers is by far the ugliest, most confrontational take on Wuthering Heights. Arnold’s use of natural light renders the indoor scenes imperceptible, while Heathcliff’s brutality gets foregrounded in a way that puts off most viewers. The film has next to no music, looks bleak as hell, and doesn’t soften Heathcliff’s sociopathy.

Like all versions discussed here other than the Wyler picture, her Wuthering Heights suffered from a rushed production. Just 18 months passed between when she first expressed interest in the project to when it premiered at Venice. Her producers encouraged the quick turnaround, despite her lack of experience working at that pace. As a result, Arnold has said the production became a series of compromises. In conversation at Tribeca 2016, she discussed a shot she particularly loathed, which felt so beautiful in her head but turned out all wrong on the day of shooting.

“I felt so unhappy, [but] I did use the shot,” Arnold said. “You have to surrender, because what can you do at that point? You’re working with a whole team of people and there’s money. You just have to accept it.”

“I find [the film] hard to look at,” she concluded.

///

“Oh! To be! In love! And never get out again…” – Kate Bush

And so we reach the present. Six adaptations from five countries across nine decades later, we find that the definitive film of Wuthering Heights does not exist. Like the book’s reputation as an epic romance, the idea is a myth. And still, the glut of adaptations continues. People want to hear this story, whether in sanitized or savage form. Filmmakers can’t help but offer their own spin on a text so ripe for interpretation. None of them succeed, and by now most know the track record on Wuthering Heights adaptations isn’t good. But like brokenhearted souls on the mend, a life of romantic failures behind them, they can’t help but try again. This time it’ll be different, they think. This time I’ll get it right.

Probably, though, you won’t. In love and filmmaking, failure finds a way. The odds are not on your side. Every day brings new opportunities to fuck up or get fucked over. Your vision for how you want your film, or your love, to be – true, pure – likely won’t materialize. The ideal and the real rarely align. More often, issues of the material world weigh us down: timing, schedules, money. Compromise. Most directors devote a few years to a film, and then they move on. Maybe they learn something about themselves. Maybe they gain some insights for the next great adventure. It’s not so different from serial monogamy.

We’re endeared by Wuthering Heights, in part, to witness a love that lasts forever. Maniacal passion kills Catherine and turns Heathcliff into a single-minded monster, but the love itself survives. Heathcliff never moves on. He doesn’t find a wife in old age or learn to live without Catherine. Time heals nothing; he doesn’t compromise. In the real world, we know humans are far less resolute. Feelings fade and people change, but not in Wuthering Heights. As Brontë tells it, feelings aren’t fleeting. This too shall not pass. Love is a fatal force, its diagnosis a life sentence. We take its wrath to the grave, and beyond. Most of us have felt the head-rush of romantic love and seen where it ends. Brontë imagines a story where it never slow-fades into a sustainable partnership or dissolution. Catherine and Heathcliff embody a love that’s pure adrenaline, like two people doing whip-its until they pass out. Their love ends spectacularly, but it doesn’t end well.

All the while, though, there is a second story here, the one filmmakers ignore or shortchange. It’s the story of Cathy and Hareton, the children who grow up in the wake of their elders’ explosive love triangle. Unlike them, these two don’t immolate in a fiery, self-flagellating passion. Instead, Cathy teaches Hareton to read, and Hareton plants Cathy a flower garden. They learn to live together as adults. They don’t burn out or fade away; they just exist, content. Their love doesn’t smolder with the same seductive intensity as Catherine and Heathcliff’s, which is why many call their portion of the book dull. It’s founded, rather, on a bond that can last in the world we live in. Theirs is not a gothic myth passed down by generations of filmmakers. It’s much more boring than that. It’s real.

Cathy and Hareton give me hope. Maybe it is possible to make these things work. Maybe next time I’ll be smarter, self-assured, more experienced. Maybe next time I’ll try harder and give more. For those drawn to the idea of adapting Wuthering Heights, I have the same message: It hasn’t worked out so far, but maybe next time.