Embracing the Unknown: ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’ By Piers Marchant

By Yasmina Tawil

The most important parts of a film are the mysterious parts – beyond the reach of reason and language. —Stanley Kubrick

Coming-of-age films generally chronicle the moment where a sexual and emotional awakening is at hand, the point at which we transition from dreamy, fun-loving kids into neurotic, beleaguered adults. (Or maybe that was just me.) If we track a bit further back from that point, however— before the characters careen all the way over the waterfall, when they can just begin to hear the distant roar ahead—there can be found a very different kind of attitude: fear of the unknown.

Peter Weir’s masterpiece, Picnic at Hanging Rock, takes us to the precipice of adulthood in the guise of a simple mystery story, by quite literally throwing some of its characters off a cliff (or at least behind one). The film opens with a long, static shot of the southern Australian desert, with small, gnarled trees and scrub brush in the foreground and a thick, hovering cloud of fog obscuring the horizon line. Gradually, the fog shifts and settles down over the trees, revealing the jutting expanse of distinctive, jagged cliffs that make up Hanging Rock, a monolithic mamelon slowly being exposed, as the ground below it becomes concealed—one of many apt metaphors Weir has in his employ.

In fact, the idea of the monolith—explored in equally confounding ways by Stanley Kubrick in his 2001: A Space Odyssey, released some seven years before Weir’s film in 1968—duly serves as the film’s linchpin, without ever disclosing its purpose or intentions. The genius of the narrative, based closely on Joan Lindsay’s novel of the same name, is in this particular kind of murkiness: Picnic can be about practically anything you want to ascribe to it. Is it a meditation on the plaintive unknown of sexual awakening? A film about the limitations of human understanding? Does it concern the idea of our intellectual and spiritual frailty? All of the above and vastly more. In the end, we have a narrative steeped in the idea of mystery at its most elemental. To do this, the film takes a form that Kubrick himself would explore in The Shining some years later: It begins simply, as a kind of genre film, but gradually opens up to a more abstract consideration of the unknown.

By taking an elegant Victorian-era mystery—three girls and their Mathematics mistress from a fancy, turn-of-the-century boarding school go missing amongst the strange, obelisk-like stone protuberances and sharply cut pathways of the Rock, after a class picnic on Valentine’s Day in 1900—and blowing up the conceit far past the point of solution, Weir has free reign to explore the obsessive conniptions we experience when presented with a true, unsolvable enigma.

He also infuses the film with a vague feeling of unease, especially in its early scenes: An obscure hum, like something out of Ridley Scott’s Nostromo, permeates the air around the Rock; the moment when the gate to the park is first opened is noted by a sudden, violent crossfade of birds shrieking across the sky over the girls’ heads; a deliberate, loud whooshing sound at peculiar junctures in the narrative jars us into believing something of great significance is about to take place, even if that doesn’t appear to be the case. All of this signifying something, we are certain, but confounding and elusive.

As the proverbial stone dropped into a flat pond, the reverberations of the disappearance continue to spread out: Michael (Dominic Guard), a wealthy young man who saw the girls begin their ascent, becomes dangerously obsessed with them, in particular Miranda (Anne-Louise Lambert), the central focal point of the incident (more on her later). The remaining classmates are terrified and baffled at first, then come to resent Irma (Karen Robson), the one girl from the missing group who has no memory of the incident, surrounding her during her last visit to the school and mercilessly haranguing her for information. Mrs. Appleyard (Rachel Roberts), the school’s headmistress, sees her enrollment plummet as a result of the incident, and feels she has no choice but to let poor Sara (Margaret Nelson) return to the abusive orphanage from which she’d been plucked some years ago, a decision that ends up causing even more tragedy.

As in Robert Eggers’ beguiling The Witch, the period setting is key to drawing our sympathy: When a filmmaker visits an earlier, less enlightened age and subjects the characters to mysterious horror, we’re forced to see the events within the constraints of the time. Early in Eggers’ film, an exiled religious family sit around a campfire in the woods. The shot, beautifully composed by Jarin Blaschke, centralizes the fire, with the flickering figures of the family huddled around it and the edges of the frame shrouded in darkness and potential threat. The film is particularly terrifying because within its context, we know as little as they do, and the horrors that befall them are every bit as inexplicable to us as they are to the doomed family who suffer through them.

Picnic, meanwhile, offers scant knowledge of Miss Appleyard’s school, residing somewhere in southern Victoria, other than the priggish nature of its Headmistress and thumbnail sketches of the students and their relationships to one another. Dreamy Sara, who has written a love poem (“Meet me, love, when day is ending…”) we quickly come to understand was written for beautiful Miranda, has found a muse, but there’s a carefully placed sense of dread in even these early scenes. Miranda warns her friend that she’ll have to learn to love someone else as she “won’t be here much longer,” a delicious bit of foreshadowing that could be read simply as an older girl facing graduation, if we weren’t otherwise clued in to the kind of thing Weir has planned for us. Still later, at the picnic, it is Miranda who announces enigmatically “Everything begins and ends at exactly the right time and place.” She is the central locus of the mystery, and seems to be aware of that before anyone else is.

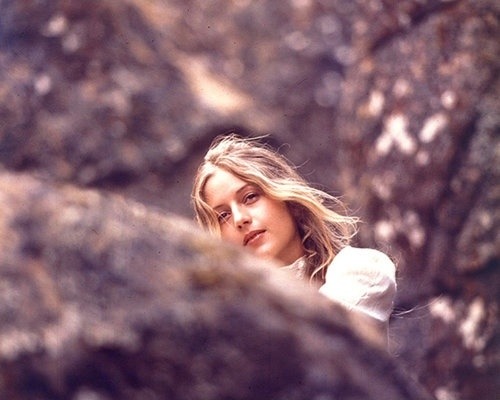

Sara is not alone in her near-obsession with Miranda: Hers is the first face we see outside of the opening exteriors of the Rock. She’s asleep, basking in heavenly morning light, pure and innocent, with just a streak of her skin visible from her nightgown as it runs horizontally out of frame. Weir’s camera suggests Miranda as the fairy tale goddess among them, and her classmates and teachers, equally besotted by her beauty and kind nature—so generous is she that she comforts poor, misbegotten Edith (Christine Schuler), who accompanies the other three girls when they go to more closely investigate the Rock, only to whine and complain about the journey (“I never thought it would be so nasty, or I wouldn’t have come!”)—do little to change the impression. Michael comes to see her as an elegant swan, who he keeps seeing in his daydreams. Her French mistress, Mlle Diane De Poitiers (Helen Morse), refers to her as a “Botticelli angel,” right as she leaves with the other doomed girls, pausing to wave goodbye beatifically at her teachers and classmates who lie around in the heat of the day, called as she is to a seemingly higher purpose.

Of course, that calling could just as well be a torturous rape and murder at the hands of an unknown assailant, for all we know. Some time later, after Michael discovers the lone survivor, Irma, her doctor assures the Headmistress that she’s “quite intact.” But the film’s ambiance not only suggests sexual overtones, it quite insists upon them, from the recurring phallic outcropping of the Rock itself to the nature of the girls’ journey to the center of the mystery. Stumbling high on top of the edifice after working their way through the twisty, winding passageways between huge blocks of stone, the girls eventually come to a small clearing, where they all fall into a deep, trance-like sleep. On peculiar cue, the three of them are awakened together and soundlessly make their way up towards the next roughhewn pathway, out of our sight. Seeing this, Edith, herself just awake and bewildered, suddenly shrieks in terror, and races back down to where her classmates still wait for them in their idyll at the base of the mountain.

That’s more or less the only information we’re ever given. We witness more than anyone other than Edith, but it’s still nowhere near enough to make a guess as to what’s happened. Weir smartly adds in particular, seemingly noteworthy details—both Miss McCraw’s watch and the pocket watch of Mr. Hussey (Martin Vaughn) stop precisely at noon, perfectly in-between the day and the night (perhaps that is the “right time” Miranda was referring to). Edith reports that she saw Miss McCraw running up toward where the girls vanished, but curiously having lost her skirt; she also vaguely remembers a red cloud—but, like something out of a David Lynch nightmare, none of these details add up to any kind of deduction. You might say they’re the kinds of hobgoblins that beset literal-minded filmgoers, many of whom were apparently less than thrilled at watching a mystery that very purposefully refused its audience the satisfaction of an explanation.

The effect of this particular consternation is profound. At once, there’s the sense of glaring disappointment—according to Weir, one Aussie film patron threw his coffee cup at the screen in disgust when the credits began to roll and belligerently demanded to know the point of a mystery without any bloody conclusion—but beyond that, a feeling that the film gets right what so many films of its genre conveniently ignore. Human culture is constantly vexed with such unanswerable mysteries: Who was Jack the Ripper? What became of the Roanoke Colony? Was Oswald the lone shooter? Is there an afterlife? We spend years, decades, centuries, millennia searching for clues, trying for definitive solutions, often to no avail, or at least not one that seems fully convincing.

As escapist entertainment, a tidily resolved mystery can be a richly rewarding experience, but just as with a love story presenting two hopelessly mismatched partners or an action movie where the hero routinely disdains the laws of physics and probability to emerge triumphant, we have to acknowledge that such outcomes are wish-fulfillment fantasies. Mismatched couples often divorce, sometimes with deep animosity; heroes die in hails of gunfire and shrapnel just like everyone else; mysteries go unsolved, leaving those directly affected no recourse but to give in to the will of the fates. “There’s some questions got answers and some haven’t,” proclaims the school’s gardener (Frank Gunnell).

For these three young women, their lives are frozen in place at the moment they leave the frame. This, then, becomes the alternative to going over that terrifying waterfall of adulthood: Vanishing from the earth and, like Anne Frank, dying young enough that the mark you make on the world becomes richly symbolic above all other things. Rather than a life actually lived, they become a life only imagined in fading memory. (As Lindsay writes in the novel’s foreword, addressing the question of whether or not it’s based on a real event, “As the fateful picnic took place in the year nineteen hundred, and all the characters who appear in this book are long since dead, it hardly seems important.”) We don’t know what happened to the women, but we do sense the totemic nature of their legacy.

The mystery in Picnic hints at so many things, but none more than the very essence of our extraordinary living arrangement, curiously stuck as we are upon this hurtling rock. To be human is to be cast into desperate ignorance. Scientists discover the smallest dust particles of pebbles, only to have them reveal even more of the impossibly large mountain range towering high above us. Religion attempts to convey the unknown in invitingly human terms that limit what we can be allowed to perceive, but deep in our souls, there remains a pervasive, gnawing feeling of incomprehension and being forced to live in that utter preposterous illiteracy every day of our lives.

Through it all, the Rock, as Melville’s ocean, remains implacable—“the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago”—and equally impenetrable. Despite our best efforts to unlock these secrets, we’re reminded, as when we look up at the vastness of the stars on a clear, moonless night, how thoroughly prepubescent our expanse of knowledge truly is. If, as the Bible hymn suggests, eventually “we’ll understand it all by and by,” it will likely come at a time when we’ll have shrugged off our mortal coil, and therefore be unable to impart this wisdom. We shall leave still ignorant the hapless creatures of the living, who stand around gazing helplessly at the glaring impenetrability of the universe.