Dr. Ryan: Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Kremlinby Daniel Carlson

By Yasmina Tawil

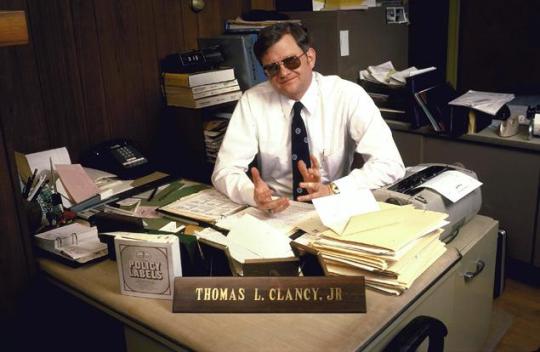

Tom Clancy was not supposed to be famous. Born in 1947, he grew up middle class in Baltimore and got an English degree from Loyola, where he joined the Army ROTC but was barred from military service because of his poor vision. After school, he got married and worked at an insurance agency that had been founded by his wife’s grandfather, and that would have been enough—would have been a fine life, indistinguishable from a million other lives—except he decided to try his hand at writing novels in his spare time. He submitted his first manuscript to the Naval Institute Press, which probably seemed like a good fit given his story’s military setting and its long stretches of dense technical descriptions. Editors persuaded him to cut a hundred pages of jargon, and that was that: released in 1984, The Hunt for Red October became a runaway hit, earning a jacket blurb from Ronald Reagan on its way to selling 45,000 copies in its first six months and more than 3 million by the time of Clancy’s death in 2013. His name became a brand for a certain kind of story—military espionage potboiler, with an emphasis on technological accuracy and a penchant for verisimilitude—and by the end of his life, his net worth was pegged at $300 million.

You do not get to make that kind of money without Hollywood noticing, and sure enough, the entertainment industry came calling not long after The Hunt for Red October made Clancy’s name a household one. The film rights were optioned in 1985, and the movie made its way to theaters in 1990. (Clancy wasn’t a fan of this or any of the movies made from his books.) This was the start of a film franchise that would continue with adaptations of additional Clancy books, in 1992’s Patriot Games and 1994’s Clear and Present Danger, at which point it essentially ended. Two attempts to reboot the series—2002’s The Sum of All Fears and 2014’s Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit—flamed out for various reasons, but those later films are also easy to ignore because they took place in different fictional universes, severed from the continuity and consequences of the earlier installments. The first three films made from Clancy books form a trilogy that revolve around the travails of Jack Ryan, a CIA analyst who finds himself drawn into increasingly dangerous situations (politically and physically) in the field, but they’re also much more. They’re fascinating aesthetic and political documents, charting America’s (and Hollywood’s) transition from the Cold War years into the morass of the war on terror. Clancy’s work came to be emblematic of a certain kind of Boomer mentality: militaristic but wary of the system, interventionist but iffy on the outcome. His breakthrough novel and subsequent successes mined the Cold War for story and emotion, but the Soviet Union disbanded not long after his career got started, leaving a vacuum into which no other clear villain could ever successfully be placed. To watch the films now, more than twenty years after the last installment, is to skip like a stone across the surface of the cultural paranoia that rippled in the wake of perestroika. They’re metaphors for themselves in many regards, and viewed through the right lens, they cohere into a single image of what it was like to live through the time of their making.

///

The first film is, inarguably, the best. Released in March 1990, The Hunt for Red October is a taut chase movie and stellar action film that never sacrifices intelligence for excitement. Alec Baldwin stars as Jack Ryan, a CIA analyst recruited to suss out the truth behind a special kind of Soviet submarine with silent-propulsion technology. The submarine in question is the Red October, piloted by Captain Marko Ramius (Sean Connery), who, disillusioned with the Soviet navy, plans to defect to the United States with a few loyal officers. His Soviet commanders, learning of this, not only begin chasing Ramius, but also tell the American National Security Adviser that Ramius plans to launch nuclear warheads into the States, thereby roping their adversaries into the hunt. Ryan is the only one who suspects Ramius’ true plan, so he sets out to intercept him before anybody else can.

There’s a beautiful simplicity in that structure, as every scene and subplot are tied to the central question: who will catch the sub? John McTiernan’s skill as a director of movies like this can’t be overstated—prior to this he’d helmed Predator and Die Hard, refining the rulebook on 1980s Hollywood action filmmaking—but he also moves effortlessly between sharply choreographed, fantastically directed action sequences and equally effective moments of character development and contemplation. There are assured, believable performances here, including Baldwin’s affable Jack Ryan, who’s scrambling to keep up with the situation at hand; Scott Glenn’s Bart Mancuso, the commander of a U.S. sub that’s pursuing Ramius; James Earl Jones’s Admiral Greer, the wise mentor who brings Jack into the situation; and Sam Neill’s Vasily Borodin, the second-in-command on the Red October who just wants to escape to a peaceful life in America. Adapted by Larry Ferguson and Donald Stewart, the screenplay strips the story to its essence, blending sociopolitical brinksmanship with thriller tropes in a way that’s consistently entertaining, even today. It was also a financial success, meaning a sequel was inevitable.

Crucially, The Hunt for Red October also benefits from a clarity of identity that’s drawn from its source material and its place on the timeline of real-world geopolitics. Even the ship’s name is designed to sound the chimes of war by referencing the Bolshevik revolution of October 1917 that presaged the formation of the USSR. Yet by the time the film came out, the Berlin Wall had started to crumble, and the Soviet Union was a year away from total dissolution. Clancy and the later screenwriters had no idea how things would work out when the story first came to life. (Indeed, the initial draft of the screenplay set the action in a then-futuristic 1991, positing “a restoration of discipline” by KGB leaders after the forced resignation of Gorbachev.) As the real USSR entered its twilight months, though, the screenplay was adjusted, and a title card was drafted for the beginning of the film that placed the story in 1984: halfway through Reagan’s presidency, and decades into a Cold War that had already shaped the minds and fears of a generation.

When Ryan first learns of the Red October’s silent-running capabilities and the implications thereof, a colleague says to him: “When I was 12, I helped my daddy build a bomb shelter in our basement because some fool parked a dozen warheads 90 miles off the coast of Florida. This thing could park a couple of hundred warheads off Washington or New York, and no one would know anything about it until it was all over.” Clancy himself was 15 during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the film’s emotional core is shaped by the feeling of what it would be like to come of age in a summer like that. The Cold War offered none of the nested alliances and cross-country relationships of the two World Wars. Rather, it was posited as a binary affair, a war of spiritual ramification and moral certitude: us versus them, freedom versus failure, enlightened democracy versus godless communism. Ramius is a sympathetic figure, but only because he wants to defect to “our” side. He doesn’t disappear into the Lithuanian countryside or resign his commission or even sabotage his military. Instead, he wants to turn the submarine over to the Americans and seek asylum in the home of the brave. The Soviets remain, throughout, definite villains. And this is also worth underscoring: the enemy here is an official geographical/political entity. It’s something you can point to on a map. There’s something almost wistful in the film, playing out a high-stakes battle when it already knows how the war will end.

Two of the film’s best moments are monologues by Ramius that lean into this. The first is the speech he gives his crew when they set out on what he tells them will be a series of missile drills off the coast of the United States. In the address (ghostwritten by John Milius), Ramius stirs his crew to cheers with his exhortation of their mission and his decrying of the fat Americans who’ll never see them coming. Each side is clearly marked with its own morality, history, and sense of purpose. The second moment is the inverse of that: a beautiful, sad, contemplative rumination on the emotional cost of the Cold War. Talking to Vasily, Ramius says, “I miss the peace of fishing, like when I was a boy. Forty years I’ve been at sea. A war at sea. A war with no battles, no monuments. Only casualties. … I widowed her the day I married her. My wife died while I was at sea, you know.” Ramius’ defection is his attempt at atonement. By 1990, such a thing could feel not just like wish fulfillment on the part of a democratically aligned nation, but as a piece of retroactive fantasy that had the benefit of being prophetic. The Hunt for Red October is the last great film of the Cold War era, and the world had already moved on by the time it arrived. Things only got messier from there.

///

When Patriot Games was released in June 1992, the world looked different. The Soviet Union had provided a clear, reliable enemy in American narrative and propaganda for decades, and its departure left a vacuum in the collective consciousness. Conflicts were no longer about protecting ourselves, but about protecting others (while securing their partnership in the endless expansion of the military-industrial complex). Instead of focusing on a silent, looming enemy that dated back to a global conflict, Americans found themselves confronting stories of terrorism and insurgent cells that defied their own governments and waged war on their own terms. The novel is set in the early 1980s, and though the film replicates the basics of the plot, it doesn’t share its timeline, and it can’t help but feel somehow softer without the looming shadow of communism to give it cultural weight. Instead of going up against the Soviets, Jack Ryan—now played by Harrison Ford, who would reprise the role in the next film—finds himself tangling with the Provisional Irish Republican Army after foiling their assassination attempt on the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

Emotionally, the film suffers from its lack of the larger sense of purpose and adventure that animated The Hunt for Red October. As a film, too, it’s weaker and less effective, and this has to do with Hollywood’s general shift at the time from 1980s action (run and gun, take no prisoners, plug in that amp and see if it goes to 11) to 1990s action (fragmented stories, awkward attempts to make everything personal, and a general bloat in which everything is half an hour too long). Red October took advantage of a simple and incredibly durable recipe for chase movies, but Patriot Games attempts to mix the cat-and-mouse thriller with the turgid family drama, and the result is as uneven as that sounds. Director Phillip Noyce, an Australian who broke through with 1988’s Dead Calm, keeps an even hand on the action for the most part, but the script (credited to W. Peter Iliff, Donald E. Stewart, and Steven Zaillian) never quite knows what to do with Ryan’s personal life, or even why it’s there.

The bulk of the movie deals with Ryan’s attempts to help the CIA capture terrorist Sean Miller (Sean Bean), who participated in the assassination attempt but escaped custody. Sean winds up injuring Ryan’s wife, Cathy (Anne Archer), and daughter, Sally (Thora Birch), in a car chase, but the sequence feels both manipulative and superfluous: Manipulative in the sense that it feels like a dishonest thing to do to viewers—Cathy is pregnant, and Hollywood movies being what they are, the odds of a pregnant woman dying on screen at the hands of a terrorist are pretty slim—and superfluous because the confrontation between Ryan and Miller is already primed on all levels. It’s politically loaded because of Ryan’s work for the CIA, and it’s personally loaded because Ryan actually killed Miller’s brother while stopping the assassination attempt, which, in addition to turning Miller against Ryan, actually makes Ryan wrestle with the human cost of what’s happening. The first film showed Ryan’s wife and much younger daughter for a single scene at the beginning—just enough to set the stage—but knew that there wasn’t enough room in the plot for the family man and the action hero. It’s possible, of course, to make a great action movie that incorporates both (McTiernan’s Die Hard being, again, the gold standard), but Patriot Games is never sure if it wants to be a thriller about revenge, a drama about a guy who happens to work for the CIA, or some nebulous third option.

The film’s lack of self-awareness, and its ultimate insecurity about its sense of purpose, comes through in the way the story comes to a close. It isn’t in a moment of triumph when he bests the villain, or even joy when he reunites with his family. Rather, the film ends with a scene of the family making breakfast in the kitchen and receiving a call from Cathy’s ob-gyn to confirm the sex of her (unharmed) baby. She asks if they want to know now or be surprised at the birth, and after a short talk, they decide they want to know now: cut to black, roll credits. The end of the film, the final narrative and emotional note toward which it has been moving, is a cliffhanger about the sex of Jack Ryan’s second baby, a sub-subplot in which almost no time and even fewer viewer emotions have been invested.

Patriot Games is an exercise in frustration precisely for how good it almost is. Ford’s approach is different from Baldwin’s, largely because he’s 16 years older than Baldwin, so his Ryan is a man more irritated than anything that all this is happening, while Baldwin more believably conveyed the essence of a man getting in over his head and taking aggressive action. Still, Ford is at his best when his character’s back is against the wall (Frantic, The Fugitive), and he feels every bit the rumpled analyst who’s smarter than everyone else in the room. Yet the film is ultimately too schizophrenic to outshine its predecessor, and today it plays like the hybrid relic that it is, stuck between eras and without an identity of its own. The franchise’s course was set.

///

The most interesting things about 1994’s Clear and Present Danger have nothing to do with the movie, and everything to do with what it represented.

The mid-1990s saw escalations in guerrilla warfare and smaller-scale armed conflicts around the world. After decades of positioning itself as the greatest bastion of freedom standing against the forces of communism, America had to deal with two grim realities: its war on drugs was a losing one, and there was no way to tell if it would ever end. The Soviets at least put a face (however abstract) on the enemy in America’s propagandistic version of its self-regard; drug lords were mysterious and invisible, and drugs seemed to be everywhere. Hollywood action movies of the era attempted to fill the void with outsize foes—it is no accident that Independence Day, a movie about aliens attacking Earth, became, vaingloriously, about America’s ability to save the world—but their aesthetics began to suffer from egotism and bloat, with heroes too hung up on their own insecurities to remember who they were supposed to be fighting. (This is when Michael Bay started directing features.)

Clear and Present Danger is as far from Red October and the heretofore expressed notion of Jack Ryan movies as could possibly be imagined, and it’s so weird and slack and ungainly that it drained any remaining blood from the franchise. Jack Ryan (Ford again), having now risen to acting Deputy Director of Intelligence, wages a paperwork war against corrupt colleagues when he realizes they’ve been secretly funding the president’s personal vendetta against Colombian drug cartels through the deployment of a black-ops team overseen by an American operative living in Colombia named John Clark (Willem Dafoe).

The film is every bit as awkward and messy as that summary would lead you to believe. There is no clear villain here, no sense of mission or drive, no easy understanding of what victory looks like, and no belief that victory can even be achieved. There are multiple plots stacked precariously atop one another: Ryan’s ascent at the CIA as a result of Greer’s sudden cancer diagnosis; Ryan’s home life, including the seconds we see him spend with the child who’s impending birth was the terminal moment of the previous film (it’s a boy), his presence clearly not as important as had been portrayed; the drug lord’s attempts to expand his empire; the efforts of the drug lord’s intelligence officer to seduce a female assistant at the CIA to solicit intel; the selection and deployment of the black-ops team, including the work of John Clark; and Ryan’s repeated travels to Colombia to try and sort out … whatever’s happening at any given moment. To call it aimless would almost do a disservice to aimlessness.

It’s the worst film of the series, easily, and not among the more memorable 1990s action movies. (It’s not even among the most memorable action films of 1994, a year that brought us Speed, The Professional, and Pulp Fiction.) But it’s fascinating for the way it perfectly captures Hollywood’s struggles in the years after the fall of the USSR to find a workable replacement villain for Soviets in narrative film. The film follows the basic model of the book it’s based upon, but the book came out in 1989, and a lot happened in the intervening five years. Even though both versions of the story are about Colombian cartels, the film feels cobbled together from disparate ideas of what action, storytelling, and drama are supposed to look like. Interestingly, John Milius was also involved with this film, writing the first draft of the screenplay, with Donald Stewart and Steven Zaillian returning from the previous film. There’s no spark or wit like the bits Milius infused into the first film, though, in large part because there’s never a real sense of purpose for Ryan here. Is he meant to save the black-ops team when they’re abandoned in the field? (He does.) Is he supposed to take a moral stand at work? (He does that, too.) Is he supposed to see justice done and evil punished? (Swing and a miss.) There’s no goal toward which the narrative’s hero can work, only a series of situations that feel tangentially connected to each other. The final third of the film finds Ryan traveling back to Colombia to connect with Clark and rescue the black-ops team, but this isn’t the point of the plot; it’s just something that happened.

It’s no wonder that the franchise died here. The film series had devolved from a propulsive, suspense-driven, emotionally resonant thriller into a baggy, compromising, confusing film that smelled of obligation. Clear and Present Danger isn’t watchable in the way Red October is, or the way any really good film is, but it’s oddly compelling in its own right because of its sheer oddness. As with Patriot Games, Noyce is enamored of resolutions that can only generously be read as ambiguous, and more honestly can be classified as flat, dull, and anticlimactic. Because there’s no real sense of closure to be achieved here, the story ends with Ryan deciding to testify before Congress about the intelligence slush funds. The final scene in the film is of him being sworn in before the panel, after which we cut to a wide shot of the crowd in the congressional chamber as the credits roll. This is the moment viewers were meant to carry with them as they left the dark theaters and walked back out into the hot parking lots of malls and multiplexes that August: the governmental oversight testimony of Jack Ryan, reluctant spy. No more emotionally charged victories over the enemy, just more paperwork. It’s an abrupt shrug of an ending, the kind of thing you get when you haven’t had a single emotional connection to anything that’s happened in the preceding two hours and just need a place to stop. So it did.

///

The two remaining Jack Ryan movies also reflect their own eras in Hollywood action filmmaking, both for the worse. The 2002 reboot The Sum of All Fears jettisons all connections to the previous films and features Ben Affleck as Jack Ryan, and it relies on generalized, non-nation-related villains to threaten the world’s safety. The film had the misfortune to be released less than a year after 9/11, which made it read like a response to the war on terror, but the reality is much less exciting. Rather, it’s the kind of technologically slick but forgettable action movie that was popular at the time, like Die Another Day, The Day After Tomorrow, and I, Robot. Conversely, the next reboot, 2014’s Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit, cast Chris Pine as Jack Ryan and actively tried to use 9/11 as a narrative prop: in its version of things, Ryan is motivated to join the Marines after the attacks, but he’s injured in battle, after which he’s recruited by the CIA. The film’s shameless incorporation of the attacks almost gels with its general penchant for nostalgia, as the Russians are the bad guys once again, time and terrorism having made it safe to mine the country for new fictional villains. This is the action film well into the era of comic book movies: a lone hero with a secret identity (Ryan works undercover at a brokerage); piles of dead bodies but no blood; lots of computer screens; the clear yet unspoken hope that this will start a new franchise, now called a “universe”; blurred action scenes that feel cobbled together from the lesser Jason Bourne films.

What’s disheartening about the two reboots is the way they complete the brand’s total disintegration. There’s no longer any sense of what a “Jack Ryan movie” might look or feel like. Rather, the character was turned into a generic protagonist, and the films lost all connection to reality as they grew safer and more anodyne. By 2014, Hollywood action filmmaking had become a mega-budget, spectacle-driven business, and there wasn’t room left for a thriller that dealt more with its characters than world annihilation. Anything less than the apocalypse was suddenly a small-stakes game, and on that scale, a handful of people trying to figure out how to help each other must not look like anything.

It’s not that there’s no such thing as a good action movie anymore, or a good espionage thriller. Rather, it’s that each Jack Ryan adventure seems to exist in a tonal world separate from the other. Action films have bombast, thrillers excel at moody drama, action films have chases, thrillers get interesting characters. It’s rare that the two meet, and fortunate that they did for at least one film here. Tom Clancy had no way of knowing the extent of the media empire he was starting when he sent his manuscript out to publishers and hoped for the best—along with films and novels, his name was licensed for video games, board games, and spinoff novels written by other people—and every empire has a fall to accompany its rise. The grand irony is that his novels started out focusing on the battle against the Soviets, hoping for victory, but that battle is what the stories needed to work. Victory brought boredom. There’s a moment in the film The Hunt for Red October when Ramius quotes Christopher Columbus as he reminisces about the home he’s lost and the one he hopes to find. Jack Ryan turns to him and says, smiling, “Welcome to the new world, sir.” It helps to think of them still out there, searching.