Comin’ (Back) At Ya: A Look Back At The 1980s’ Brief, Bizarre 3-D Movie Boom By Noel Murray

By Yasmina Tawil

A few months ago, Flicker Alley released the Blu-ray anthology 3-D Rarities, collecting some of cinema’s early 3-D experiments, alongside shorts and trailers from the format’s 1950s heyday. Those first, furtive efforts are especially fun. In brief tests and demo reels made in the 1920s, pioneers like Jacob Leventhal, William van Doren Kelley, Frederic Eugene Ives, and William T. Crespinel tried to see if cinema could replicate or even improve on the optical tricks familiar to photography buffs. Some of their films presented simple stereoscopic tableaus—nature scenes, tourist travelogues, and the like. But others were more gimmicky. Their actors were encouraged to break the front plane frequently and boldly, thrusting lassos, guns, feet, fishing poles, flowers, and hot dogs toward the viewer.

When Hollywood started producing 3-D features in earnest between 1952 and 1954—partly as a way of competing with television—filmmakers mostly used the technology of the time the way that directors do today, mainly aiming to create a sense of depth. But 3-D retained a reputation for being, well… jabby and pokey. Long after the craze died down, whenever comedians wanted to parody 3-D, they’d brandish a pitchfork or fling projectiles toward the camera. And the few remaining producers who still made 3-D films between 1954 and the early 1980s tended to specialize in the tawdry, promising cheap thrills that would literally get right in the audience’s face.

Then in 1981, a European production company partnered with Filmways in the U.S. to bring 3-D back with the grubby R-rated western Comin’ At Ya! But director Ferdinando Baldi and writer-producer-star Tony Anthony stuck with the clichéd version of the process that the public had been led to expect from so many bad jokes. Even Comin’ At Ya’s opening credits are like a trip through an amusement park haunted house, as Anthony’s bandit anti-hero pours dried beans at a tilted-up camera, and fires a bullet toward the audience (in a moment that could be a nod to Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 classic The Great Train Robbery, which legendarily had early moviegoers ducking from a gunshot). Comin’ At Ya! is mostly a belated, belabored entry in the spaghetti western genre, though because Baldi and Anthony used 3-D to liven it up, they ended up making something that’s a visual experience first and foremost, with no dialogue at all in the first 12 minutes. It’s only after the film plays on for a while that all the slow-motion debris, blinding lens-flares, and worm’s-eye-view shots of dangling objects start to lose their novelty.

When Comin’ At Ya! became a surprise hit, some movie producers rushed to capitalize on what looked like it could be the next big thing (or, more accurately, an old big thing, newly revived). For roughly the next four years, every few months, new 3-D movies showed up, falling generally into three categories:

THE SMALL-TIMERS

A year after Comin’ At Ya! came out, Baldi and Anthony sold their services to the B-picture impresarios at Cannon Films, and made the 1983 Raiders Of The Lost Ark ripoff Treasure of the Four Crowns. The built more elaborate sets than they’d had on Comin’ At Ya!, and employed a richly atmospheric Ennio Morricone score. But otherwise, the follow-up was a fairly shameless attempt to copy their prior success, right down to the long dialogue-free passages and the many, many low-angle shots of objects falling. Treasure of the Four Crowns failed to become much of a sensation, perhaps because aside from the 3-D effects, it didn’t really seem all that special. It was just another here-and-gone exploitation film.

There was a mini-wave of those kinds of 3-D pluggers in the early 1980s: films like 1982’s Rottweiler: The Dogs of Hell (a threadbare eco-horror exercise, about military trained killer dogs on the loose), the same year’s Parasite (a post-apocalyptic monster movie starring a young Demi Moore and The Runaways’ former lead singer Cherie Currie) and 1984’s Silent Madness (a poorly acted thriller about a maniac on the loose). Most of these have faded into oblivion, though some can be found on YouTube or file-sharing sites. They’re not great—though there’s something entertainingly gonzo about both Parasite and Treasure of the Four Crowns—but they’re interesting as examples of how low-budget filmmakers are often businessmen first and foremost, always yoking themselves to trends. All of these films likely would’ve existed even without the 3-D resurgence. But because they were trying to squeeze out a little more box office, their creators made them more assaultive.

THE BIG SWINGERS

Some producers saw an opportunity with the 3-D revival to make something elaborate, ambitious, and immersive. By the time Spacehunter: The Adventures in the Forbidden Zone came out in the summer of 1983, the public fascination with the process was already dimming, which is a shame. Spacehunter’s a mess—an overstuffed, kitchen-sink mix of post-Star Wars science-fiction and dusty post-apocalyptica—but it’s at least teeming with interesting visual ideas. Director Lamont Johnson and his production designers came up with intricate sets and ornate costumes, which have a real sense of dimensionality even in 2-D. And while the plot’s muddled, it’s no dopier than Avatar. The film is kind of the forerunner of the more thoughtful 3-D action-adventures of today.

The same could be said of Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn, and the animated Starchaser: The Legend of Orin. The unifying characteristic of all these films is that while they’re primarily intended as spectacle, there’s more to them than just the sight of people flinging detritus about.They mean to create a world that the audience can enter, rather than pushing us away with sharp sticks and rubble.

THE SEQUELS

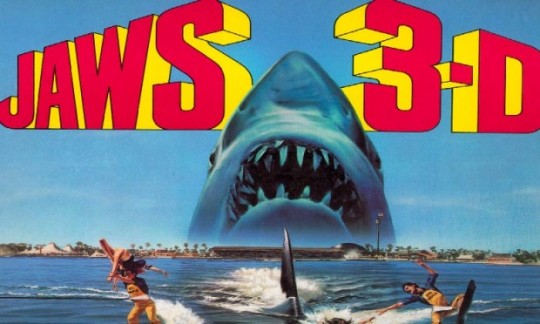

Due largely to an accident of timing, the 1980s 3-D craze—brief as it was—dovetailed with multiple movie franchises hitting their third installments. Ergo: Amityville 3-D, Jaws 3-D, and Friday the 13th Part III (which avoided the “3-D” tag mainly because it would’ve been an awkward fit with the rest of the title… although Paramount did put “A New Dimension In Terror” on the posters, above a picture of a knife thrusting forward). These films are the products of the 1980s 3-D boom that have endured the longest, if only because completist fans of those series feel obliged to watch them. They’re also the films that expose the weaknesses of the format—at least it was being used post-Comin’ At Ya!.

The third Friday the 13th is actually mildly enjoyable, because it’s the first film in the franchise to have a sense of humor, and because jump-scares are super-effective when they’re accompanied by flying eyeballs, harpoons, and yo-yos. Amityville 3-D, on the other hand, just dresses up a moronic haunted-house plot with a surplus of extreme-foreground light fixtures and fluttering critters. (Really, the movie’s best effect isn’t anything 3-D, but rather the performance of a young Meg Ryan, who peps up the proceedings whenever she appears.) As for Jaws 3-D, its director Joe Alves—formerly a production designer—makes an effort to use the process to create a kind of “submerged in a cinematic aquarium” feel, which is laudable. But his lighting is too dim, and his green-screen laughably lousy.

It’s strange to watch these movies now, because they’re rarely shown in 3-D. Instead, they’re pop up on cable just like any other Jaws or Friday the 13th picture, and when they do, the plane-breaking seems all the more superfluous. (It’s also easy to spot when these moments are about to happen, because the overall image gets murkier and blurrier.) The sequels take a reductive approach to the concept of 3-D, not unlike how television variety shows used to do “a salute to silent movies” that devolved into pie-fights—as though that was the defining shtick of geniuses like Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin, and Buster Keaton. In the early 1980s, the enthusiastic experiments of early-to-mid 20th century 3-D gave way to something dully pro-forma.

In part because of the shoddiness of the product—and in part because of the inadequacy of the technology—the Comin’ At Ya! era was brief, mostly petering out by the end of 1983, aside from a few stragglers. Later in the decade, 3-D was consigned more to amusement park attractions and IMAX theaters, where technicians started developing the better-quality cameras and glasses that paved the way for today. Here in the early 21st century, 3-D is routinely offered as a negligible enhancement for most blockbuster movies—although occasionally we do get an Avatar, Hugo, or Pina, made by a visionary director who has given serious thought to the purpose behind the extra dimension.

Still, most filmmakers of 2015 could learn something by studying the likes of Parasite, Metalstorm, and Amityville 3-D. Given how long this latest iteration of 3-D has endured, it’s hard to call the format a “fad,” the way it was in the 1950s and 1980s. But how many times a year does a movie come out that has to be seen in 3-D? Directors and producers aren’t leaning on the technology as a stunt anymore, which is probably good for the shelf-life of their product at least. But too few are really thinking about how to use the format to amaze.

And that could be a problem down the road, because sometimes in planning for the conversion process, directors put limits on what they can do. Joss Whedon has talked about this with his Avengers movies, how he had to limit close-ups and quick-cuts during the action sequences. If 3-D ever does go away again, all those Marvel movies may look as curiously off-kilter as Jaws 3-D does now. Will movie buffs of the 2040s wonder why all our blockbusters had such tiny heroes, moving so slowly? Are filmmakers sacrificing playfulness for the sake of turning out more Dogs of Hells?