“Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai?”: Bollywood's Scandalous Question, and The Hardest-Working Scene in Movies by Genevieve Valentine

By Yasmina Tawil

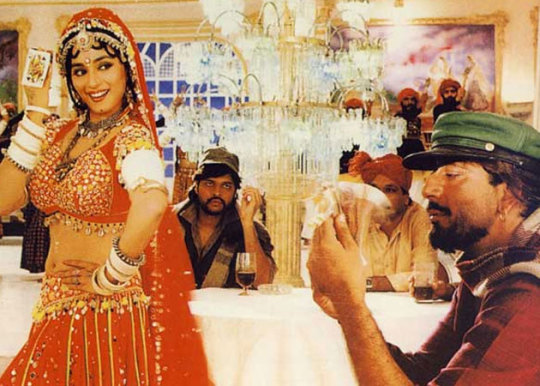

In a nightclub with the mood lighting of a surgical theater, a village belle is crying out for a husband. Her friend Champa encourages and chastises her by turns; her male audience is invited to be the bells on her anklets. (She promises, with a flare of derision, that serving her will make him a king.) Her costume, the color of a three-alarm fire, sparkles as she holds center screen. The song and camerawork builds to a frenzy as if unable to contain her energy; the dance floor’s nearly chaos by the time she ducks out—she alone has been holding the last eight minutes together. And the hardened criminal in the audience follows, determined not to let her get away.

Subhash Ghai’s 1993 blockbuster Khalnayak is a “masala film,” mingling genre elements with Shakespearean glee and a healthy sense of the surreal. By turns it’s a crime story, a separated-in-youth drama, a Gothic romance with a troubled antihero, a family tragedy, a Western with a good sheriff fighting for the rule of law, and a melodrama in which every revelation’s accompanied by thunder and several close-ups in quick succession. (There’s also a bumbling police officer, in case you felt something was lacking.) It was a box-office smash. But the reason it’s a legend is “Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai?”—“What’s Behind That Blouse?”— an iconic number that’s one of the hardest-working scenes in cinema.

See, Ganga (Madhuri Dixit) isn’t really a dancer for hire. She’s a cop gone undercover to snag criminal mastermind Ballu (Sanjay Dutt), who’s recently escaped from prison and humiliated her boyfriend, policeman Ram (Jackie Shroff). Ballu, undercover to avoid detection, is trying to avoid trouble on the way to Singapore…but of course, everything changes after Ganga.

Though the scene shows its age—the self-conscious black-bar blocking, the less-than-precise background dancers—it’s an impressive achievement. Firstly, it’s a starmaker: the screen presence of Madhuri Dixit seems hard to overstate. By 1993 she was already a marquee name, and she would dominate Bollywood box office for a decade after, both as a vivid actress and as a dancer whose quality of movement was without peer. But if you’d never seen a frame of Bollywood you’d still recognize her mountain-climb in this number—playing the cop who disdains Ballu playing the dancer trying to court him, performing by turns for the room and to the camera, conveying flirty sexuality without tipping into self-parody, and all on the move for kinetic camera shots ten to fifteen seconds at a time. Dixit’s effortless magnetism holds it fast; the camera loves what it loves.

But this is more than just a career-making dance break; “Choli Ke Peeche” is the film’s cinematic and thematic centerpiece. Khalnayak is about performativeness. Ballu performs villainy (sometimes literally) in the hopes it will fulfill him; Ram vocally asserts the role of virtuous cop to define himself against those he prosecutes. As Ballu performs good deeds—saving a village from thugs, ditching his bad-guy cape for sublimely 1993 blazers—his conscience grows back by degrees. As Ganga performs a moral compass for Ballu, her heart begins to soften. And at intervals, crowds deliver praise or censure, reminding us that all the world’s a stage. (It’s in the smallest details: While on the run, Ballu’s ready to kill a constable until it turns out he’s an extra in the movie shooting down the street.)

And nowhere in cinema is the fourth wall more permeable than a musical number. Bollywood’s turned them into an art. Playback singers are well-known (they even have their own awards categories), a layer of meta in every performance. Diegetic dance numbers are common. Movies often halt the action entirely for an item number, as a guest actress drops by. For the length of a song, the suspension of disbelief the rest of a movie requires is on pause.

Musical numbers are a place where a movie can comment on itself, and Khalnayak takes full advantage of the remove. (In an earlier number with more traditional Hollywood framing, Dixit winks at us while singing to her beloved.) Likewise, Saroj Khan’s choreography in “Choli Ke Peeche” invites us to enjoy Ganga’s sexuality without concern about racy lyrics—or even about the villain, who dances in his chair along with the rest of us. With the camera as chaperone, it’s safe for “Ganga” to asks what else she’s meant to do but lift her skirts a bit as she walks (that skirt’s expensive!), and to let her prince know she sleeps with the door open. The men around her are either part of the act, or an audience safely contained by the narrative and the frame for our benefit. (At times, her back is to her audience so she can dance for the camera; Khalnayak knows we’re watching.) “Choli Ke Peeche” is a thesis statement on the relationship between performance and audience.

It’s a moment powerful enough to cast a shadow across the rest of the film. This number, not the crimes or the cops, is what the movie returns to repeatedly; it’s too good to ignore and too subversive to solve. Not least, among the other layers of performance, is queer subtext. In Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures, Gayatri Gopinath points out that “female homoerotic desire between Dixit and [Neena] Gupta is routed and made intelligible through a triangulated relation to the male hero.” Champa’s masculinized within the performance; she asks the loaded title question, addresses our heroine’s male savior, and discusses him with Ganga. It’s a significant connection between women in a song supposedly directed at a man—which might be why Champa is the one who defends Ganga’s reputation by explaining the dance-hall sting, and reminding the audience it was all for show.

But that’s not going to stop “Choli Ke Peeche.” At the end of the second act, Ballu blows Ganga’s cover. (He’s known she’s a cop since their backstage meeting—another layer of performance). To prove they mean no real harm, the men don lenghas and veils and parody a chunk of the number, right down to interjectional close-ups and a wandering camera that brings kinetic energy to the static space.

In one way this reprise tries to undercut the song’s power by making it faintly ridiculous, suggesting it isn’t really sexual—it’s camp. But if “Choli Ke Peeche” functioned as a ‘safe’ way for Ganga to express sexuality when we first saw it, it serves a parallel purpose here. Despite the mocking undertones, with this number the men are reassuring her; they understand her sexuality was itself just a performance—her purity is therefore safe with them. (We know that’s a concern here because her shawl is pulled close about her; the free-spirit act is over, and her virtue is at stake.)

But there’s also something undeniably subversive in hyper-masculine, violent figures reenacting coy expressions of feminine desire. To prevent things from getting too subversive, Ballu invades Ganga’s personal space, a reminder of his power amid the making fun. And the performance ends in the threat of violence against Ganga when she breaks the spell—the expected order of captor and captive reestablishing itself as the film falls into a formulaic last act, an attempt to wrest social order out of the exuberant chaos one musical number has wrought.

It caused some chaos offscreen, too. When the soundtrack was released ahead of the film, “Choli Ke Peeche” was deemed obscene; the song was banned on Doordarshan and All India Radio, and faced legal challenge at the Central Board of Film Certification. In “What is Behind Film Censorship? The Kahlnayak debates,” Monika Mehta writes that “the visual and verbal representation combined to produce female sexual desire. It was the articulation of this desire that was the problem—it posited that women were not only sexual objects, but also sexual subjects.” And within the number, there’s no doubt Ganga’s in control; she sends alluring glances Ballu’s way, mocks (then takes) his money, and signals he’s free to follow her if he dares. The undercover-cop framework gives these gestures the veneer of respectability, but since Ballu doesn’t know that yet, the frisson of the forbidden remains.

Letters of condemnation and support rolled in. Many claimed the song was too suggestive; an exhibitor from Paras Cinema in Rajasthan wrote in favor because “Choli Ke Peeche” was based on a folk song from the area, and “If it was vulgar then the ladies would have never liked it.” The examining committee eventually ruled in favor of letting the number remain, with some edits: one that removed the chorus entirely (which Ghai successfully appealed), and two cuts to beats considered provocative, including one of Ganga ‘pointing at her breast’ as she sings, “I can’t bear being an ascetic, so what should I do?”, unequivocally claiming sexuality without even a man as her object. No wonder it had to go.

It wasn’t the only controversy dogging the film; star Sanjay Dutt was arrested under The Terrorist and Disruptive Activities Act for possible connections to the 1993 Bombay bombings, which added an uncomfortable self-awareness to Ballu’s onscreen misdeeds. Yet those controversies did Khalnayak no harm at the box office, where it broke records, and the movie’s had such nostalgic power that as of 2016, Ghai was considering a sequel.

But “Choli Ke Peeche” remains the movie’s most measurable influence. In Bombay Before Bollywood: Film City Fantasies, Rosie Thomas notes that after Ganga, “distinctions between heroine and vamp began to crumble, as the item number became de rigueur for female stars,” suggesting Khalnayak was a harbinger of less rigid strictures for Bollywood’s leading ladies. Another legacy of Khalnayak: more numbers feature women—with a man as the absent locus of their affections—dancing with each other instead, forming their own narrative connections and opening the opportunity for queer readings. (One of the most famous, “Dola Re Dola” from 2002’s Devdas, features Dixit again, alongside costar Aishwarya Rai.)

The pressure of so much cultural influence and metatextual weight might have turned a lesser scene into a relic, a stuttery car chase from a silent movie that starts a montage of the ways the camera has developed. It’s a testament to “Choli Ke Peeche” that it absorbs the weight of the years as gracefully as it does. If you want a watershed moment for sexual agency in Bollywood, you have it. If you want a starmaker with dancing that’s influenced choreography and direction for twenty years since, it’s happy to help. If you want a scene that dissects the idea of performance as subversive act, the offscreen vulgarity scandal only adds to your case. And if you want a musical number that reminds you what cinema can do, “Choli Ke Peeche” is as vibrant, campy, and complex as ever.